Event

The wind blew fiercely from the southeast, raising the Ionian waters into tumult and gushing with foaming the crested waves. Restless and dark, the sea hurled itself with fury against the rugged cliffs of Karaburun. Draped in black clouds, the sky looked utterly hopeless. Amid the storm, a Byzantine ship with tattered sails and a broken mast fought desperately against the mounting waves. Onboard the ship, outstanding, none other than Emperor John Palaiologos. Frantically searching for shelter and escaping utter destruction, a glimmer of light in the storm-worn faces of the crew emerged as then, amidst the savage rocks, the Karaburun hidden bay suddenly revealed itself.

The next morning, the tempest had subsided. The sun slowly illuminated the damp rock faces, revealing ancient inscriptions — forgotten names, prayers of sailors and wishes of travelers who had once anchored in that very bay. The Emperor stood silently before them for a long time. Hope and fear were eternally carved into stone.

Those traces from visitors past reminded him that, in the face of nature and the lot of fate, man — even an emperor — remains but fragile. He decided to leave his own mark upon the rock. He did not carve a prayer or a plea, but a simple testimony: that in the distant year 6877 of the Byzantine calendar, he too had stood there, like so many before him, facing the same blind force. This was a profoundly human gesture, a sign marking his being there, facing storm and fear and experiencing the fragile spark of hope.

When the ship was ready to depart, the sun was already rising above the now-calmed Ionian waters. John Palaiologos cast one last look at the inscription he had left behind, then turned — without a word — toward the open sea. The voyage to Rome had begun: a journey of final hope toward the shores of the Adriatic, where, in the halls of the Vatican, Pope Urban V still kept alive the faint light of belated aid.

The next morning, the tempest had subsided. The sun slowly illuminated the damp rock faces, revealing ancient inscriptions — forgotten names, prayers of sailors and wishes of travelers who had once anchored in that very bay. The Emperor stood silently before them for a long time. Hope and fear were eternally carved into stone.

Those traces from visitors past reminded him that, in the face of nature and the lot of fate, man — even an emperor — remains but fragile. He decided to leave his own mark upon the rock. He did not carve a prayer or a plea, but a simple testimony: that in the distant year 6877 of the Byzantine calendar, he too had stood there, like so many before him, facing the same blind force. This was a profoundly human gesture, a sign marking his being there, facing storm and fear and experiencing the fragile spark of hope.

When the ship was ready to depart, the sun was already rising above the now-calmed Ionian waters. John Palaiologos cast one last look at the inscription he had left behind, then turned — without a word — toward the open sea. The voyage to Rome had begun: a journey of final hope toward the shores of the Adriatic, where, in the halls of the Vatican, Pope Urban V still kept alive the faint light of belated aid.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

Historical period: From the 3rd century BCE to the 15th century CE (and even into modern times)

Historical overview of the period

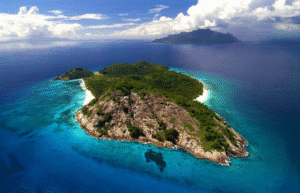

The Bay of Grama, positioned on the western side of the Karaburun Peninsula and facing Sazan Island, has been known since antiquity as a natural refuge for ships during storms — and as a site where fresh, drinkable water could be found. Its name, Grama, derives from the Greek gramma (“inscription”), owing to the hundreds of carvings engraved into the rock by sailors, soldiers, pilgrims, captains and ordinary travelers who had at a point sought shelter there.

With its secluded position at the southern tip of Karaburun, the bay represents one of the most unique sites of Albania’s spiritual heritage whereby the sea, man and faith resound. Though rooted in historical fact, the site has acquired mythical and sacred dimensions within the collective memory of sailors from Albania and beyond.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

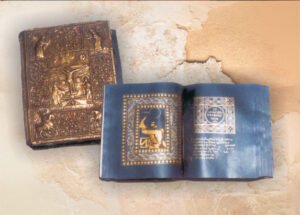

Originally exploited as a quarry, the cliffs of Grama preserve more than 1,500 inscriptions, carved from the 3rd century BCE onward. The latest belong to the medieval period, including Latin inscriptions from the imperial epoch and centuries after. Most of them are dedicated to the Dioscuri — Castor and Pollux, divine protectors of sailors and ships. The inscriptions generally follow a similar formula, where the author seeks divine help for companions, relatives, crewmates or fellow soldiers.The travelers came from both nearby and distant lands — Asia Minor (Ilion, Phocaea, Heraclea Pontica) and even Palestine (Sebastia).

Among the many names, we find references to historical figures, such as Gnaeus Pompeius, rival of Julius Caesar (49–48 BCE). The most remarkable document dates from 1369 CE, recording the stay of John Palaiologos, Emperor of the Romans, who sought refuge in the bay before continuing toward Venice and later Rome, where he met Pope Urban V to secure aid amid the worsening situation in Constantinople and the advance of Ottoman forces.

Message

The Bay of Grama stands as both a natural and spiritual sanctuary for the people of the sea — a place of reverence and communion with the divine in confronting the unknown expanse of the waters. In facing the immense forces of nature and the decline of an empire, even an emperor is reduced to the essence of humanity: seeking meaning, hope and eternity not in the vestiges of power, but rather through a single trace left upon stone.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Today, the Bay of Grama is considered by many as “the place where the stone speaks,” an open archive symbolizing the natural and historical refuge where humans find protection and reflection. It represents the connection between the past and the present, the power of nature that challenges human authorities, and the hope for meaning amid life’s challenges.

Bibliography

- CIGME III: Cabanes, Pierre; Drini, Faik; Hatzopoulos, M. (coll.), Corpus des inscriptions d'Albanie (en dehors des sites d’Épidamne-Dyrrhachion, Apollonia et Bouthrôtos), École française d’Athènes, Paris, 2016.

- Hajdari, Arben; Reboton, Joany; Shpuza, Saimir; Cabanes, Pierre, Les inscriptions de Grammata (Albanie), Revue des Études Grecques 120 (2007), pp. 353–394.

- Oral heritage archive, Institute of Folk Culture, “Karaburun–Grama” collection, recordings gathered between 1970–1985.