Event

Church bells rang through the cold dawn of that early winter morning. Their sound echoed from the walls of Sarda, rolled down the jagged hills, drifted across the calm waters of the Drin River, and reached — faint and solemn — the outskirts of Koman.

That morning, by the riverbank, kin from a family old as the very the stones of the city, gathered to lay their patriarch to rest. He had been more than a leader. He had been a guardian of traditions and memory preserving the very name of the land, with a devotion akin to that of preserving words woven in the songs of ancestors. His passing away was more than a death. Amid the silent grief and restrained tears in the final preparations, they placed on his hand a bronze ring engraved with a symbol — the eagle — heirloom of generations past. It was not merely a family mark, but an emblem of heights, strength and irrepressible freedom of spirit.

— “He will be buried with it,” said the eldest of the house. “Just so as he lived — with the eagle at his heart.”

The bells tolled louder, as if following the rhythm of the hearts left behind — hearts convinced that the symbol would not vanish with his body. For the eagle does not live in bronze. It lives through memories cherished by generations, the unyielding courage not to bow, the pride of deep roots and the strength to soar high.

The bells fell silent, but the mist lingered over the valley. Within it resounded memory itself — carved like an eagle — rooted in the land where ancestral bones rest and still living in the remembrance of those whose name shall be voiced across centuries.

That morning, by the riverbank, kin from a family old as the very the stones of the city, gathered to lay their patriarch to rest. He had been more than a leader. He had been a guardian of traditions and memory preserving the very name of the land, with a devotion akin to that of preserving words woven in the songs of ancestors. His passing away was more than a death. Amid the silent grief and restrained tears in the final preparations, they placed on his hand a bronze ring engraved with a symbol — the eagle — heirloom of generations past. It was not merely a family mark, but an emblem of heights, strength and irrepressible freedom of spirit.

— “He will be buried with it,” said the eldest of the house. “Just so as he lived — with the eagle at his heart.”

The bells tolled louder, as if following the rhythm of the hearts left behind — hearts convinced that the symbol would not vanish with his body. For the eagle does not live in bronze. It lives through memories cherished by generations, the unyielding courage not to bow, the pride of deep roots and the strength to soar high.

The bells fell silent, but the mist lingered over the valley. Within it resounded memory itself — carved like an eagle — rooted in the land where ancestral bones rest and still living in the remembrance of those whose name shall be voiced across centuries.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

10th–12th centuries CE

Historical overview of the period

The ancient settlement of Koman, located in the middle valley of the Drin River, spreads across several steep hills at altitudes of 600–700 meters, covering a total area of about 40 hectares. While disappearing in the 16th century following the Ottoman conquest, it bears witness to a major medieval city and an important diocese of the early Arbër civilization. The site features three levels — upper, middle, and lower — and its defining topographic feature is the presence of two churches, one in the lower and one in the upper part of the settlement, both serving as spiritual and communal centers for their respective populations.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

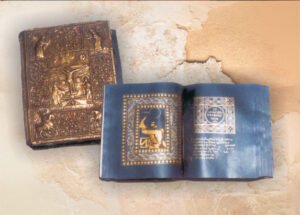

The necropolis lies near the churches, reflecting the deep connection between life, faith and funerary ritual. It represents one of the largest burial areas of its period, with tombs rich in grave goods. Studies show that the family played a central role in managing and preserving the burial place as a site of collective memory over multiple generations. Their strategies of remembrance appear in architecture (such as tomb structures conceived for successive reuse) and in the social dimension by way of accumulation and transmission of wealth and symbolic artifacts. Recent excavations at the Koman necropolis have uncovered several bronze rings engraved with a single-headed eagle. This discovery is significant for understanding the cultural and identity features of the population that inhabited the region during the early medieval period.

The eagle has long been a powerful symbol in Albanian culture, with meanings that evolved over centuries. In the context of Koman, the single-headed eagle, depicted on funerary rings, likely carried protective or identity-related significance, especially for individuals of elevated social rank. Its presence in burial contexts reveals not only its symbolic importance in daily life but also its function as a marker of cultural belonging and collective memory after death. These findings offer tangible evidence of the strong cultural and identity continuity linking the inhabitants of Koman with the enduring emblem of Albanian heritage.

Message

This piece conveys a timeless truth: memory does not die. It lives on in the soil that preserves the traces of the ancestors, in the symbols passed down from one generation to the next, and in the hearts of generations following. The eagle — carved in bronze and alive in collective remembrance — embodies freedom, strength and endurance.

Meaning in Today’s Context

In a rapidly changing reality to which we must adapt, the eagle—as a symbol of freedom, strength, and resilience—reminds us that identity is not only heritage but also a responsibility that requires awareness and dedication. To remember means to remain connected to the land, to history, and to those values that do not fade with time, but through it, gain significance.

Bibliography

- Nallbani, Etleva. “Early Medieval North Albania: New Discoveries, Remodeling Connections,” in Adriatico altomedievale (VI–XI secolo), 2017.

- Nallbani, Etleva; Gallien, Véronique. “Inhumation et statut social privilégiés dans l’Ouest des Balkans au haut Moyen Âge. Les cas de Lezha et Komani,” in De Vingo, Paolo; Marano, Yuri; Pinar Gil, Joan (eds.), Sepolture di Prestigio nel bacino mediterraneo (secoli IV–IX), All’Insegna del Giglio, Sesto Fiorentino (FI), 2021, pp. 473–494.

- Nallbani, Etleva et al. Komani. Peuplement et territoires dans l’occident balkanique (VIe–XVe s.). Komani, Sarda et Lezha: Campagnes de fouilles et d’études 2020–2021, Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l’étranger, 2023.