Event

On a crisp morning, the youngest men of the village set out at the order of the council’s elder to look for a stone. It had to be round, firm, no larger than a man’s fist but not small so as to be prone to being lost. The stone would serve as the witness to an oath — the pledge of men who had just taken a decision vital to the fate of their entire katund (community). They had vowed to stand together against a foreign threat to their freedom.

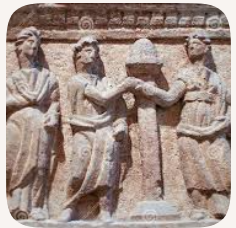

When the stone was found and brought with due care to the assembly, the plaku i madh (the eldest of the council) held it in his hand for a long moment, looking each man in the eyes. All stood in a semicircle, silent and solemn. Then he passed the stone to the first man on his left. That man placed it in the palm of his left hand, touched it with his right, and declared in a clear voice: “For the goodness of God, so may He help me, neither I nor any of my household shall ever break faith with the village.” One by one, each man repeated the same formula.

When the stone returned to the elder, he too swore upon it. Then, raising his hand high, he said: “He who breaks this oath, may his head break as I now release this stone.”

And he let the stone fall to the ground before the eyes of the assembly of men. From that moment, the stone was no longer ordinary. It carried the weight of word, honor and besa. It was kept in the elder’s house as a sacred object. People would say, “This is no longer a mere stone — upon it an oath was sworn and it shall be guarded as a consecrated thing.” To discard it or treat it carelessly was deemed a grave sin.

The oath upon the stone (beja mbi gur) was not used only for collective decisions. In many cases, it served as the ultimate act to prove an individual’s innocence. A man accused of betrayal, falsehood or another grave offense could request to swear upon the stone to clear his name of the blemish. The oath was inviolable: if a man swore falsely, it was believed that within three days the earth itself would punish him.

In Mirdita this practice took on an almost mystical dimension. The stone was not only a witness but considered a saint, as it were. In Albanian culture, the stone held a dual status as both a physical boundary and a sacred medium. Stones marked borders, graves, council grounds and, most importantly, oaths of honor. In regions such as Mirdita, Labëria and Dukagjini, “gurët e besës” (stones of the pledge) are still remembered as sites where historic oaths were made to end blood feuds, seal alliances or unite against foreign enemies.

When the stone was found and brought with due care to the assembly, the plaku i madh (the eldest of the council) held it in his hand for a long moment, looking each man in the eyes. All stood in a semicircle, silent and solemn. Then he passed the stone to the first man on his left. That man placed it in the palm of his left hand, touched it with his right, and declared in a clear voice: “For the goodness of God, so may He help me, neither I nor any of my household shall ever break faith with the village.” One by one, each man repeated the same formula.

When the stone returned to the elder, he too swore upon it. Then, raising his hand high, he said: “He who breaks this oath, may his head break as I now release this stone.”

And he let the stone fall to the ground before the eyes of the assembly of men. From that moment, the stone was no longer ordinary. It carried the weight of word, honor and besa. It was kept in the elder’s house as a sacred object. People would say, “This is no longer a mere stone — upon it an oath was sworn and it shall be guarded as a consecrated thing.” To discard it or treat it carelessly was deemed a grave sin.

The oath upon the stone (beja mbi gur) was not used only for collective decisions. In many cases, it served as the ultimate act to prove an individual’s innocence. A man accused of betrayal, falsehood or another grave offense could request to swear upon the stone to clear his name of the blemish. The oath was inviolable: if a man swore falsely, it was believed that within three days the earth itself would punish him.

In Mirdita this practice took on an almost mystical dimension. The stone was not only a witness but considered a saint, as it were. In Albanian culture, the stone held a dual status as both a physical boundary and a sacred medium. Stones marked borders, graves, council grounds and, most importantly, oaths of honor. In regions such as Mirdita, Labëria and Dukagjini, “gurët e besës” (stones of the pledge) are still remembered as sites where historic oaths were made to end blood feuds, seal alliances or unite against foreign enemies.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

An ancient Albanian tradition, documented since the 17th century, with much deeper oral and customary roots.

Historical overview of the period

In the Albanian highlands, words were not mere sounds — they were acts. In the absence of written law, a spoken promise carried the weight of a sacred contract. Among all forms of oath, the most solemn was the “oath upon the stone,” a practice deeply rooted in Albanian moral and customary life as the embodiment of truth, honor and justice. The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini recognizes this “beja mbi gur” as one of the most solemn and honorable oaths known to man, equal in sanctity to swearing upon the Gospel itself.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

In a society where honor and manhood formed the foundation of authority, disputes, agreements and reconciliations required no judges but rather only witnesses: the men of the assembly and the earth that overheard them. The stone, as symbol of permanence and of the sacred bond between man and earth, served as the medium to ground the word and ensure it could never be undone. The oath was made with one’s hand upon the stone, in the name of God and of the shame that would befall upon the perjurer.

Message

The oath upon the stone is not a mere custom, but a profound expression of Albanian moral culture — where justice, honor and community intertwine. It embodies collective conscience and the sacred will to preserve one’s word as something inviolable. Through this ritual, speech transcended the personal and became a sacred debt owed to the earth and to others. Its consequences extended beyond this life into the next. The oath upon the stone forged one of the strongest links between man, land and honor. The oath was not simply a verbal act, but rather a wholesome commitment, a moral contract witnessed not just by people, but nature itself – earth, stone and sky. In a world where justice depended on faith rather than punishment, the “beja mbi gur” upheld the moral and social structure of communal life, making each man responsible for his word and deeds.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Today, when the law is written and court decisions prevail above all else, an oath sworn upon a stone may seem like a relic of the past. Although today’s legal system is built upon documents, laws, and institutions, the oath endures in other forms — in language, in collective memory, and in symbols. Expressions like “I’ve given you my word” or “I’ve sworn upon bread and salt” preserve the essence of this culture. They recall a time when a word carried more weight than a seal, and a promise needed no proof — only trust.

Bibliography

- Gjeçovi, Shtjefën. Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit [The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini]. Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese “Idromeno,” 1993.

- Tirta, Mark. Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë [Mythology among the Albanians]. Tiranë, 2019.

- Elsie, Robert. Albanian Folktales and Legends. London: Dukagjini Publishing House, 2001.