Event

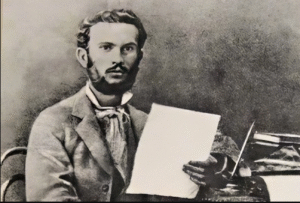

On his journey toward the Holy Land, the knight Arnold von Harff came ashore on the Albanian coast, in Durrës. In his travel diary, he wrote that the city had strong walls, lively trade and a mixed population of Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Muslims. Yet what struck him most was the language he heard spoken there.

Von Harff was a tireless traveler and chronicler of the world he encountered. He had crossed mountains and seas, writing in Greek, Turkish, Italian...

An old man with a white qeleshe cap called out to his son in words that seemed carved out in stone:

— Eja, bir! Buka është gati. (Come, son! The meal is ready.)

The knight looked up. He could not understand the words, yet he felt their weight. Turning to the innkeeper, he asked,

— “What language do these people speak?”

— “They speak Shqip,” the man replied. “It’s the language of our stone.”

Intrigued by the unfamiliar sounds, Arnold began to collect words, asking for translations and carefully noting them in his travel book: vene, krup, criste, kale, myreprema... [wine, salt, crest, horse, good evening…] In his diary, he wrote in Old German: “Item dese stat lijcht in Albanijen dae sij ouch eyn eygen spraiche haynt, der man nyet wael geschrijuen en kan, as sij geyn eygen liter in deme lande en hauen.”(This city, Durrës, lies in Albania, where they also have their own language, which cannot be written well, for in this land they have no letters of their own.)

“These are words,” he whispered to himself, “spoken by a people who may lack paper, yet possess a soul”… “It is a language I may never understand, but I will preserve it — for those who come after.”

As he looked toward the mountains, he added to his diary: “The inhabitants are strong, silent and stern. They bow to no one. The language they speak is unlike any other I have heard. They call it Shqip.”

That night, in a remote corner of a fragmented empire, words Albanians became committed to writing for the first time.

Words that Arnold von Harff recorded were no mere strange sounds to foreign ears, but also invisible threads of our collective memory — words of a language guarded within the bosom of people’s hearts across centuries.

Von Harff was a tireless traveler and chronicler of the world he encountered. He had crossed mountains and seas, writing in Greek, Turkish, Italian...

An old man with a white qeleshe cap called out to his son in words that seemed carved out in stone:

— Eja, bir! Buka është gati. (Come, son! The meal is ready.)

The knight looked up. He could not understand the words, yet he felt their weight. Turning to the innkeeper, he asked,

— “What language do these people speak?”

— “They speak Shqip,” the man replied. “It’s the language of our stone.”

Intrigued by the unfamiliar sounds, Arnold began to collect words, asking for translations and carefully noting them in his travel book: vene, krup, criste, kale, myreprema... [wine, salt, crest, horse, good evening…] In his diary, he wrote in Old German: “Item dese stat lijcht in Albanijen dae sij ouch eyn eygen spraiche haynt, der man nyet wael geschrijuen en kan, as sij geyn eygen liter in deme lande en hauen.”(This city, Durrës, lies in Albania, where they also have their own language, which cannot be written well, for in this land they have no letters of their own.)

“These are words,” he whispered to himself, “spoken by a people who may lack paper, yet possess a soul”… “It is a language I may never understand, but I will preserve it — for those who come after.”

As he looked toward the mountains, he added to his diary: “The inhabitants are strong, silent and stern. They bow to no one. The language they speak is unlike any other I have heard. They call it Shqip.”

That night, in a remote corner of a fragmented empire, words Albanians became committed to writing for the first time.

Words that Arnold von Harff recorded were no mere strange sounds to foreign ears, but also invisible threads of our collective memory — words of a language guarded within the bosom of people’s hearts across centuries.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

Late 15th century (around 1496)

Historical overview of the period

By the end of the 15th century, Albania stood at one of its most perilous crossroads. The organized resistance against the Ottoman Empire had collapsed. Fortresses were falling one after another. Skanderbeg had passed into legend and thousands of Albanians were migrating toward Italy, Arbëria e Poshtme (Lower Arbëria), and beyond. The darkness of conquest and exile seemed to engulf everything. Yet even under that boding shadow, the Albanian language persevered as a light that could not be extinguished — unwritten in books but spoken on every doorstep, preserved in songs, whispered in curses and adorning prayers. It was the language of blessing and mourning, the language of greeting and of besa. At this very moment, a young knight from Cologne — Arnold von Harff — traveled through Albanyen, as he called it, and without realizing it, left behind one of the earliest written records of the Albanian language. In his travel chronicle, amidst descriptions of cities, shrines and medieval customs, he paused to record words of a tongue unlike any other he had heard — a language he identified as “albanische spraiche” (Albanian language).

Conditions that gave rise to the event

In December 1496, Arnold von Harff set sail from Italy and landed at Durrës, on his pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He was not a conqueror but a traveler driven by faith and curiosity, eager to describe the world as he saw it. While documenting the towns and landscapes along his route, he encountered something entirely new: a language spoken by locals that matched none of the tongues he knew — not Latin, Greek, Slavonic, nor Turkish.

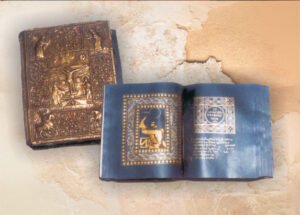

Von Harff transcribed what he could — a small handful of words — perhaps unaware that he was creating a linguistic monument. His short notes represent the earliest external testimony to the Albanian language, written decades before the famous Formula e Pagëzimit (“Baptismal Formula”) recorded by Pal Engjëlli in 1462.

Message

The Albanian language was not born in royal courts or imperial chancelleries. It was not decreed into existence — it was sung, wept, whispered and shouted. It lived in the voices of mothers, the songs of shepherds, the blessings of weddings and the cries of warriors in the battlefield. Scholars did not invent it. People preserved it. A language existing before writing itself — and precisely because it lived, it survived.

At the close of a turbulent century, the foreign knight Arnold von Harff paused, listened and put down into writing a few Albanian words. For us today, this personal act of a knight writing strange words in his diary acquires the proportions of a monumental testimony to the Albanian language by now a national official language written and spoken across continents. This episode reminds us that a language is not only a means of communication but a living memory, an act of survival and a heritage of spiritual creation.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Today, when the Albanian language is official, written, widespread in the diaspora, and internationally recognized, this small episode — a knight who wrote a few Albanian words in his diary — takes on the dimensions of a great testimony. It reminds us that this language is not merely a means of communication, but a living memory, an act of survival, and a spiritual creation. Preserving the language has been the most sublime act this people have performed through the centuries. When there was no freedom, there were words. When there were no schools, there were songs. When there were no books, there were mouths that told stories, women who blessed, men who sang, children who learned in hidden homes. And thus, the Albanian word survived in silence, with dignity, never extinguished.

Bibliography

- Arnold von Harff. Die Pilgerfahrt des Ritters Arnold von Harff von Cöln durch Italien, Syrien, Egypten, Arabien, Ethiopien, Nubien, Palästina, die Türkei, Frankreich und Spanien (1496–1499). Ed. E. von Groote. Köln: M. DuMont-Schauberg, 1860.

- Çabej, Eqrem. Hyrje në historinë e gjuhës shqipe [Introduction to the history of the Albanian language]. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, 1982.

- Elsie, Robert. Historical Dictionary of Albania. Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- Shuteriqi, Dhimitër. Shkrimet e para shqipe dhe humanizmi shqiptar [The first Albanian writings and Albanian humanism]. Tiranë: Naim Frashëri, 1974.