Event

It is said that on dark nights, when the northern wind blows and the waves crash against the rocks, at the Cape of Rodon one feels as though time has stopped and that, with a little imagination, one can almost see the figures and events of centuries gone by. Ancient legends tell of a mysterious light that once shone upon the cliff — a beacon for sailors lost at sea. This light, once believed to be a blessing from unknown deities, was to be later seen as a sign of divine protection and hope. It is no coincidence that two of Albania’s most precious monuments — Skanderbeg’s Castle and the Church of St. Anthony (Shën Ndou) — were built on this very cape.

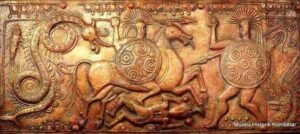

Around 1451–1452, after a period of alternating war and peace with the Ottoman Empire. Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu chose this solitary, strategic site near his capital Kruja to erect a fortress. Independent from Venetian control, the castle would serve as a secure exit to the sea in case the army needed to retreat or else for ease of communication with western allies. The historian Marin Barleti records that Skanderbeg had even begun building a small city there, which he called “Kjurilë” or “Chiurilium”. The Ottomans later found it deserted and unfinished — and razed it to the ground. Barleti also recounts that Skanderbeg once spent part of the summer and autumn at Rodon with his wife, enjoying hunting and leisure at a time when warfare did not demand his immediate presence.

The fortress, built upon solid terrain, had thick walls descending from the hill down to the coast, forming an unsurmountable shield against any assault. Venetian travelers and later Albanian scholars described it as a work of great military foresight. Though only fragments now remain in silent defiance of centuries gone by, the outer defensive wall measured 100 meters long, ending at the sea and featuring two round towers. The fortress was destroyed by the Ottomans in 1467 and later repaired by the Venetians in 1500.

A few hundred meters from the castle, nestled between two hills, stands the Church of St. Anthony of Padua (Shën Ndou). Built in the Middle Ages, perhaps atop an earlier sacred site, it became a center of pilgrimage and prayer for hundreds of believers. For many Albanian Catholics, St. Anthony’s Day is the time they return here seeking healing, blessing and spiritual peace. Near the church there once stood a monastery. Historical records mention both the Monastery of St. Mary and the Monastery of St. Anthony, one of the earliest Franciscan convents known since 1599. The monks who lived there were revered for their wisdom and life in harmony with nature. They aided villagers, prayed for sailors and gave the entire region a sense of sanctity. Old accounts tell that during stormy nights, the monks would light candles so their glow might guide ships through

the darkness — a gesture perhaps continuing a much older tradition, when fire was lit on the same spot to guide sailors across the sea.

In this small stretch of land above the waters, war and peace, earthly struggle and spiritual devotion, are deeply intertwined. Here, Skanderbeg built his fortress to protect the land, while the faithful raised a church to safeguard the soul. And between these two monuments, the wind still blows, carrying with it the voices of many ages past.

Around 1451–1452, after a period of alternating war and peace with the Ottoman Empire. Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu chose this solitary, strategic site near his capital Kruja to erect a fortress. Independent from Venetian control, the castle would serve as a secure exit to the sea in case the army needed to retreat or else for ease of communication with western allies. The historian Marin Barleti records that Skanderbeg had even begun building a small city there, which he called “Kjurilë” or “Chiurilium”. The Ottomans later found it deserted and unfinished — and razed it to the ground. Barleti also recounts that Skanderbeg once spent part of the summer and autumn at Rodon with his wife, enjoying hunting and leisure at a time when warfare did not demand his immediate presence.

The fortress, built upon solid terrain, had thick walls descending from the hill down to the coast, forming an unsurmountable shield against any assault. Venetian travelers and later Albanian scholars described it as a work of great military foresight. Though only fragments now remain in silent defiance of centuries gone by, the outer defensive wall measured 100 meters long, ending at the sea and featuring two round towers. The fortress was destroyed by the Ottomans in 1467 and later repaired by the Venetians in 1500.

A few hundred meters from the castle, nestled between two hills, stands the Church of St. Anthony of Padua (Shën Ndou). Built in the Middle Ages, perhaps atop an earlier sacred site, it became a center of pilgrimage and prayer for hundreds of believers. For many Albanian Catholics, St. Anthony’s Day is the time they return here seeking healing, blessing and spiritual peace. Near the church there once stood a monastery. Historical records mention both the Monastery of St. Mary and the Monastery of St. Anthony, one of the earliest Franciscan convents known since 1599. The monks who lived there were revered for their wisdom and life in harmony with nature. They aided villagers, prayed for sailors and gave the entire region a sense of sanctity. Old accounts tell that during stormy nights, the monks would light candles so their glow might guide ships through

the darkness — a gesture perhaps continuing a much older tradition, when fire was lit on the same spot to guide sailors across the sea.

In this small stretch of land above the waters, war and peace, earthly struggle and spiritual devotion, are deeply intertwined. Here, Skanderbeg built his fortress to protect the land, while the faithful raised a church to safeguard the soul. And between these two monuments, the wind still blows, carrying with it the voices of many ages past.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

From Antiquity to the 20th century

Historical overview of the period

The Cape of Rodon, also known as the Cape of Skanderbeg’s Muzhli, on the Adriatic coast, has for centuries long served as a point where nature, defense and faith converge. With its elongated shape stretching into the sea formed by land eroded by winds and water, this promontory has drawn attention since antiquity: from ancient sailors to medieval warriors and monks. Today, it preserves the remains of a castle built by Skanderbeg, according to Marin Barleti, and the ruins of the Church of St. Anthony, one of the most sacred pilgrimage sites for Albanian Catholics.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

The Cape’s location is a gift from nature allowing anyone seeking to see far into the horizon, to defend from enemies or else to find refuge for the soul. Surrounded by the sea on three sides and separated from the mainland by wooded hills, the cape has long been both protected and secluded — ideal for strategic fortifications. Though erosion has reshaped its vestiges over time, the stories embedded in its soil and stone endure to-the-day.

Message

The Cape of Rodon embodies the continuity of Albanian history encompassing the struggle for survival and defense and the enduring search for peace and faith. It is more than a geographic landmark, for it is a meeting point between land, sea and transcendence. Today, the cape is one of Albania’s most visited places, prompting admiration not only for its natural beauty but also for its historical and spiritual resonance. It invites every visitor to pause, gaze beyond the horizon and listen to the quiet testimony of its stones — which still speak of the nation’s shared heritage.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Today, Cape Rodon is one of the most visited places in Albania, not only for its natural beauty but also for its historical and spiritual significance. It invites every visitor to pause, to look beyond the horizon, and to listen to the story told by its stones — a story that belongs to everyone.

Bibliography

- Barleti, Marin. Historia e Skënderbeut [The History of Skanderbeg]. Tiranë: Instituti i Historisë, 1967.

- Fjalori Enciklopedik Shqiptar [Albanian Encyclopedic Dictionary]. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, Tiranë, 1985.