Event

In Delvina, a town scarred by long wars for freedom and survival, there once lived a man named Gjin Aleksi. He did not seek glory, yet impressed deeply. A local leader, a Christian by faith and passionately devoted to the soil of his ancestors, Gjin Aleksi was a man who built when others destroyed.

It is said that he labored to raise two churches — those of Rusan and Papuçia. It is also said that though he spoke little, his words carried weight. During that time, construction carried a meaning far greater than one might today imagine, for a well-placed stone could stand for centuries.

But not long after, another more imposing power would encroach upon Albania’s territories: the Ottomans. They came not merely as conquerors, but also as bearers of a new order founded upon foreign laws and a foreign faith. Many who had until then prayed in churches now faced a difficult choice: leaving their homeland or else adapting to this new religion. Some abandoned their churches and others conformed.

According to local oral tradition, Gjin Aleksi resolved not to leave the fate of his people in the hands of strangers. He accepted the new faith, yet that was not a renouncing in spirit. He resolved that as he had once built for Christians, he would now for Muslims — not out of devotion to the Sultan or in pursuit of wealth, but out of responsibility toward his people.

That morning, having made his decision, Gjin Aleksi descended to the village square, where the men awaited him. His words were few but firm: “I am not changing neither the memory of our forefathers, nor that of my homeland. I am changing only the way I will defend this land. Here, where we once built for the soul, we shall build again — a new house of the prayer for this new time. But the stones will be ours, and my name will remain above the gate. Are you with me?”

Old Lekë, who had raised three sons in that same neighborhood, lifted his head and spoke slowly, almost whispering, yet his words clearly reaching all present: “And you, Gjin — will you pray with us?”

He answered: “I will pray that this land never curses us — that we never forget who we are, even when our appearance changes. I will be with you. But this is not a man’s promise — it is the promise of our whole country. What unites us is our language, our traditions and our customs, not our faith.”

Then Tanush, once a servant in Gjin’s household, spoke up: “If it is by your hand and not that of strangers, and if it will rise from our own stones — then yes! If you lead us, we will follow!”

The next day, work began. Stones and clay, walls rising again, hands carving with care, work flowing through deep understanding though no words spoken. On that hillside, the small community of Delvina built its mosque with the revering silence for the past and the patience demanded by the present.

Today, when one passes through Delvina and looks up toward the old mosque on the hill, with its stones unmoved by centuries gone by, one feels a quiet peace that is not born out of grandeur, but rather humbleness. That mosque does not speak loudly, yet it speaks truthfully: telling the story of a troubled time when a man chose not to vanish away, but instead adapt without forsaking who he was.

It is said that he labored to raise two churches — those of Rusan and Papuçia. It is also said that though he spoke little, his words carried weight. During that time, construction carried a meaning far greater than one might today imagine, for a well-placed stone could stand for centuries.

But not long after, another more imposing power would encroach upon Albania’s territories: the Ottomans. They came not merely as conquerors, but also as bearers of a new order founded upon foreign laws and a foreign faith. Many who had until then prayed in churches now faced a difficult choice: leaving their homeland or else adapting to this new religion. Some abandoned their churches and others conformed.

According to local oral tradition, Gjin Aleksi resolved not to leave the fate of his people in the hands of strangers. He accepted the new faith, yet that was not a renouncing in spirit. He resolved that as he had once built for Christians, he would now for Muslims — not out of devotion to the Sultan or in pursuit of wealth, but out of responsibility toward his people.

That morning, having made his decision, Gjin Aleksi descended to the village square, where the men awaited him. His words were few but firm: “I am not changing neither the memory of our forefathers, nor that of my homeland. I am changing only the way I will defend this land. Here, where we once built for the soul, we shall build again — a new house of the prayer for this new time. But the stones will be ours, and my name will remain above the gate. Are you with me?”

Old Lekë, who had raised three sons in that same neighborhood, lifted his head and spoke slowly, almost whispering, yet his words clearly reaching all present: “And you, Gjin — will you pray with us?”

He answered: “I will pray that this land never curses us — that we never forget who we are, even when our appearance changes. I will be with you. But this is not a man’s promise — it is the promise of our whole country. What unites us is our language, our traditions and our customs, not our faith.”

Then Tanush, once a servant in Gjin’s household, spoke up: “If it is by your hand and not that of strangers, and if it will rise from our own stones — then yes! If you lead us, we will follow!”

The next day, work began. Stones and clay, walls rising again, hands carving with care, work flowing through deep understanding though no words spoken. On that hillside, the small community of Delvina built its mosque with the revering silence for the past and the patience demanded by the present.

Today, when one passes through Delvina and looks up toward the old mosque on the hill, with its stones unmoved by centuries gone by, one feels a quiet peace that is not born out of grandeur, but rather humbleness. That mosque does not speak loudly, yet it speaks truthfully: telling the story of a troubled time when a man chose not to vanish away, but instead adapt without forsaking who he was.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

16th–17th centuries.

Historical overview of the period

The 16th and 17th centuries brought decisive religious and cultural transformations across Albania. As Ottoman rule consolidated, many regions experienced a gradual transition from Christianity to Islam. This process was neither uniform nor linear, but unfolded over generations as an interplay of political, economic, social and spiritual factors. While the construction of new mosques signaled the spread of Islam, many older churches were adapted for rites of the new creed, reflecting not only the religious but also a continuity of collective memory. Within this context, the Mosque of Gjin Aleksi in Delvina stands as an emblematic case where faith intertwines with historical remembrance.

According to ethnographic records collected in the 1950s–1960s, Gjin Aleksi is remembered as an active historical figure as the Ottoman empire verged upon and advanced towards southern Albania — a Christian local leader of Delvina who fought both Ottoman and Venetian forces. Oral tradition recounts that he built two churches, those of Rusan and Papuçia, which after the Ottoman conquest were later transformed into mosques.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

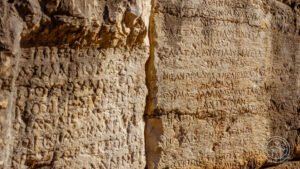

The Mosque of Gjin Aleksi was constructed upon the foundations of an earlier church. Visitors describe it as one of the most distinctive religious monuments for its architectural fusion, its structure preserving traces of its previous Christian vestiges – a feature common to many Balkan religious edifices transformed during the centuries long period of Islamization. Situated on an elevated site in Delvina, the mosque was built with finely carved stones. Its windows and columns reflecting the Byzantine church influence, while the dome and minaret being later Ottoman additions. This material evidence confirms that the building was not raised entirely anew, but adapted with modest changes to accommodate Islamic worship.

Message

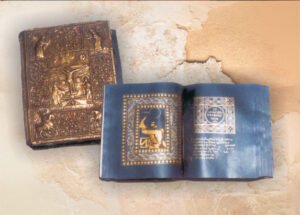

The Mosque of Gjin Aleksi is far more than a religious monument. It is a meeting point between historical memory and cultural adaptation, embodying the efforts of communities striving to preserve their past while embracing new realities. The retention of a Christian leader’s name on an Islamic sanctuary reveals a deep sense of historical continuity and mutual respect — a local testament to coexistence rather than obliteration.

The Christian founder’s name featured in the building in follow-up to its transformation into a mosque represents a layered cultural heritage, where collective memory survived religious conversion and evolved into a symbol of tolerance, continuity and shared identity.

Meaning in Today’s Context

In today’s world, where religious wars and differences often cause division, the story of Gjin Aleksi highlights one of the greatest values of the Albanian people — religious tolerance. What matters is not the building, whether a mosque or a church, but the shared faith in one God. It is the harmony of the community in having a common ritual and a shared place to pray to God. Many peoples choose to leave, but the resistance of our ancestors to remain is the very foundation of our heritage.

Bibliography

- Kiel, Machiel. Ottoman Architecture in Albania. Istanbul: IRCICA, 1990.

- Elsie, Robert. Historical Dictionary of Albania. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- Institute of Anthropology, “Lluka Karafili Collection,” Oral Traditions and Legends from Southern Albania, 1950–1960.