Event

When the traveler named Dorian arrived at a village sewn into the slopes of the Albanian Alps, he did not know that he had stepped into another world — one where footsteps respect the past and the word of honor does not die with the body. He had come to photograph mountain landscapes for his archive, but instead of the views he awaited to open up to him, he suddenly heard a deep, rhythmic and trembling sound.

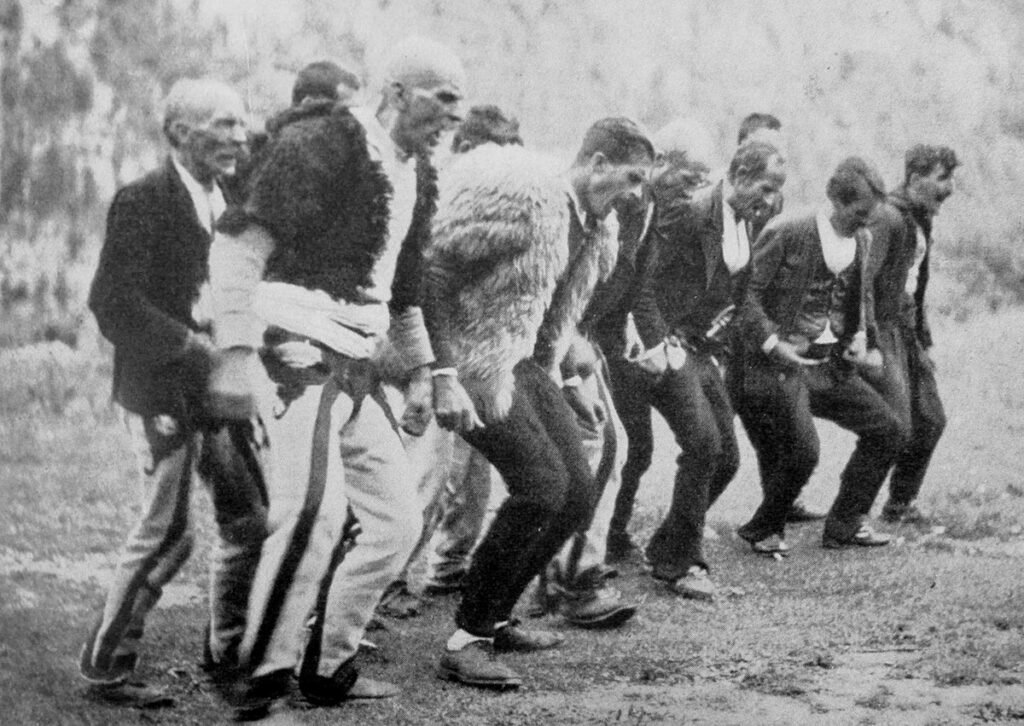

It was the men’s lament — “gjama e burrave”. He did not ask anyone what was happening. All stood silent. From the upper road a line of men descended solemnly toward the courtyard of a house where the body of an honorable elder lay covered.

. At the entrance, the women sat apart, weeping quietly, while the men formed a circle and bowed slightly, each placing a hand on his chest. One man stepped forward, white-mustached, with deep eyes and a presence that spoke louder than words. There were no musical instruments or rehearsals and that was no spectacle. There was but voice. The first man began releasing rhythmical sounds that were neither a song nor a simple outcry. They were words that struck like stones blowing upon the chest of the still air. They were both a curse against death and a praise to life.

“Ah man of the earth, you have fallen with great honor; you have torn our hearts, yet your trace shall not vanish from this soil!”

!” One after another, the others joined in perfect rhythm, synchronizing not by virtue of rehearsal but rather custom, altogether forming a chorus lamenting an ancient sorrow. The traveler stood motionless. Even his camera dared not make a sound. He realized he was witnessing no mere mourning but a rare procession, a collective rite of manly grieving, a tradition emerged not to act out a drama of sorts but rather ensure that pain did not die with the body.

In northern Albania and also in Labëria, gjama was the only way men were allowed to lament. Tears were forbidden and their sorrow could not flow down their faces but instead rise through words hurled toward the sky. Their forefathers had set this rule: men do not weep — they grieved like men. The ritual had its own laws.

. Gjama was not performed for just anyone. It was reserved for men of integrity, wise, just and noble. The community decided in silence who was worthy of such an honor. It was the final tribute to a life lived righteously, with no word or besa ever broken.

Everything unfolded with the gravity of an ancient procession. The men stood with hands on their chests or heads, as if restraining something mounting within and verging on gushing forth. At the peak of the lament, with voices united in their highest pitch, Dorian felt himself tremble — not from sadness, but from awe instilled by a culture that had found a language of farewell that preserved dignity even in the face of overwhelming grief.

When it was over, no one spoke. The men sat on nearby stones, drank a small glass of raki in silence and then departed. They had done their part. They had carried their fellow brother beyond — with voice.

The traveler turned to an old man and asked, “What was that?”

The elder looked at him calmly and said, “That was the last word — but heavier than all others. What the mouth can no longer say, the gjama says.”

Today, many of these laments are no longer heard – the young having left the hearth and modern funerals replacing ancestral rites. Yet in remote villages, when a man of honor dies, six or seven men will still rise together, shaking the air with their voices. Gjama is not merely sound — it is the soul rising and resounding in final glory.

It was the men’s lament — “gjama e burrave”. He did not ask anyone what was happening. All stood silent. From the upper road a line of men descended solemnly toward the courtyard of a house where the body of an honorable elder lay covered.

. At the entrance, the women sat apart, weeping quietly, while the men formed a circle and bowed slightly, each placing a hand on his chest. One man stepped forward, white-mustached, with deep eyes and a presence that spoke louder than words. There were no musical instruments or rehearsals and that was no spectacle. There was but voice. The first man began releasing rhythmical sounds that were neither a song nor a simple outcry. They were words that struck like stones blowing upon the chest of the still air. They were both a curse against death and a praise to life.

“Ah man of the earth, you have fallen with great honor; you have torn our hearts, yet your trace shall not vanish from this soil!”

!” One after another, the others joined in perfect rhythm, synchronizing not by virtue of rehearsal but rather custom, altogether forming a chorus lamenting an ancient sorrow. The traveler stood motionless. Even his camera dared not make a sound. He realized he was witnessing no mere mourning but a rare procession, a collective rite of manly grieving, a tradition emerged not to act out a drama of sorts but rather ensure that pain did not die with the body.

In northern Albania and also in Labëria, gjama was the only way men were allowed to lament. Tears were forbidden and their sorrow could not flow down their faces but instead rise through words hurled toward the sky. Their forefathers had set this rule: men do not weep — they grieved like men. The ritual had its own laws.

. Gjama was not performed for just anyone. It was reserved for men of integrity, wise, just and noble. The community decided in silence who was worthy of such an honor. It was the final tribute to a life lived righteously, with no word or besa ever broken.

Everything unfolded with the gravity of an ancient procession. The men stood with hands on their chests or heads, as if restraining something mounting within and verging on gushing forth. At the peak of the lament, with voices united in their highest pitch, Dorian felt himself tremble — not from sadness, but from awe instilled by a culture that had found a language of farewell that preserved dignity even in the face of overwhelming grief.

When it was over, no one spoke. The men sat on nearby stones, drank a small glass of raki in silence and then departed. They had done their part. They had carried their fellow brother beyond — with voice.

The traveler turned to an old man and asked, “What was that?”

The elder looked at him calmly and said, “That was the last word — but heavier than all others. What the mouth can no longer say, the gjama says.”

Today, many of these laments are no longer heard – the young having left the hearth and modern funerals replacing ancestral rites. Yet in remote villages, when a man of honor dies, six or seven men will still rise together, shaking the air with their voices. Gjama is not merely sound — it is the soul rising and resounding in final glory.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

An ancient practice, clearly documented from the 18th to the mid-20th century.

Historical overview of the period

In Albania’s patriarchal society, especially in the North and Labëria, pain, honor and death were events laden with deep social meaning. Within this context developed gjama, a male-exclusive collective form of lament — neither song nor cry, but a structured, rhythmic and ceremonial outpouring. It gave men a legitimate and honorable way to express grief in societies where public tears were forbidden. Beyond mourning, gjama served as a moral message celebrating integrity, courage and continuity. It affirmed the deceased’s reputation and reminded the living of the values binding the community together.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

In the absence of formal rituals or written culture, gjama emerged as a collective emotional outlet — a way to channel grief with dignity, discipline and shared participation. It allowed men to manifest affection and loss while preserving the composure demanded by the moral codes of the time.

Message

Gjama is not merely a lament but a ceremony of remembrance and respect — a voice that binds community, morality and emotion into a single act. It transforms grief into continuity, turning pain into collective strength. Through gjama, Albanian men found a dignified way to express emotion without surrendering to it. It is a testament to balance — between restraint and expression, sorrow and honor — and anb enduring reminder that even silence can have a voice.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Today, the "gjama" has become rare and in some areas has disappeared, but its memory remains a powerful testament to how Albanian men experienced loss and grief. It is part of the national spiritual heritage and should be preserved as a cultural treasure that speaks of identity, dignity, and the ethics of Albanian expression. Through the "gjama", we understand that even the strongest voices have the right to cry out for losses that cannot be forgotten.

Bibliography

- Tirta, Mark. Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë [Mythology among the Albanians]. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, Tiranë, 2004.

- Gjeçovi, Shtjefën. Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit [The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini] — commentary on funeral rites and customs.