Event

In a remote mountain village, where the shadows of old trees covered the paths and the murmur of flowing streams mingled with the song of nightingales, there lived a people who listened to nature as they would heed a parent or a saint. They walked through the forest with great care, touched no branch for no reason and never raised their voices in the grove for, as the elders said, “that is where the god of the animals rests.” In that place, everything was believed to have a soul: the earth, the grass, the water — even the stones. But above all else one creature was never to be harmed — the roe deer. They called it “the blessed one of the forest” and “the spirit that sees but does not speak.”

The oldest among them, old Dodë, remembered a distant summer when his grandfather had told him of a roe deer that once appeared near the mountain hut. It had come down alone, having left its herd, fearless –quenching the thirst in the rushing spring, to then return to the woods without turning the head back to looking. “Do not touch it,” the grandfather had said. “It is sacred. It comes in times of peace or when men have forgotten to fear their own selves.”

But time passes — and with it comes forgetting. Rituals become habit, habits grow old, and memories fall away like autumn leaves. One summer, when water was scarce and the livestock weakened, the young men of the village decided to venture higher into the mountains to hunt. Among them was Leka, a quiet and thoughtful youth who had often heard people call the roe deer “a sacred creature,” though sometimes also “a rare meat for the table.” It had been years since anyone had seen a roe deer in those parts and the forest seemed to call them.

After a long day of tracking in the depths of the densest woods — where sunlight barely broke through the leaves — a roe deer appeared. Graceful, slender-necked and gleaming-skinned, it looked straight at the hunters and did not move. It showed no fear. Its stillness was unsettling.

“It’s not prey — it’s an omen,” murmured someone.

But a shot rang out. A single crack — and the roe deer fell. Silence followed. Leka, who had pulled the trigger, was the first to approach. The deer was not yet dead. Its breath trembled, its eyes teared. They were eyes other than those of an animal. The were eyes that questioned and seemed to probe into the soul.

“He’s crying,” whispered Leka and his blood froze. He knelt beside the creature and said nothing. Not a word even when his fellows called him to lift the body. Not even when they urged him to celebrate. That evening, by the fire, as the meat roasted and cups clinked, Leka sat apart and spoke only one sentence: “Can’t you feel it? Something that was with us — is now gone.”

These words demanded no further elaboration. From that night onwards, no one in the village ever went hunting for roe deer again. Nor did anyone raise a gun against the wild goats which at times came nearby at the break of dawn. When they passed through the shaded grove, they walked with bowed heads and whispered, “There, in its shadow, the roe deer awaits not to be forgotten.”

.” The mountain understood. A year later, when the grass grew tall and green, old Dodë saw another roe deer pause at the very same brook. A different deer, surely — yet it carried the same serenity. A being that asked for nothing, merely that it not be harmed.

Since that day, no one in that village has ever raised the hand against a roe deer. When outsiders come to hunt, the locals tell them the story of The Broken Feast and say: “The roe deer is not meat. It is sacred. If you kill it, you have stepped upon your very self.”

The oldest among them, old Dodë, remembered a distant summer when his grandfather had told him of a roe deer that once appeared near the mountain hut. It had come down alone, having left its herd, fearless –quenching the thirst in the rushing spring, to then return to the woods without turning the head back to looking. “Do not touch it,” the grandfather had said. “It is sacred. It comes in times of peace or when men have forgotten to fear their own selves.”

But time passes — and with it comes forgetting. Rituals become habit, habits grow old, and memories fall away like autumn leaves. One summer, when water was scarce and the livestock weakened, the young men of the village decided to venture higher into the mountains to hunt. Among them was Leka, a quiet and thoughtful youth who had often heard people call the roe deer “a sacred creature,” though sometimes also “a rare meat for the table.” It had been years since anyone had seen a roe deer in those parts and the forest seemed to call them.

After a long day of tracking in the depths of the densest woods — where sunlight barely broke through the leaves — a roe deer appeared. Graceful, slender-necked and gleaming-skinned, it looked straight at the hunters and did not move. It showed no fear. Its stillness was unsettling.

“It’s not prey — it’s an omen,” murmured someone.

But a shot rang out. A single crack — and the roe deer fell. Silence followed. Leka, who had pulled the trigger, was the first to approach. The deer was not yet dead. Its breath trembled, its eyes teared. They were eyes other than those of an animal. The were eyes that questioned and seemed to probe into the soul.

“He’s crying,” whispered Leka and his blood froze. He knelt beside the creature and said nothing. Not a word even when his fellows called him to lift the body. Not even when they urged him to celebrate. That evening, by the fire, as the meat roasted and cups clinked, Leka sat apart and spoke only one sentence: “Can’t you feel it? Something that was with us — is now gone.”

These words demanded no further elaboration. From that night onwards, no one in the village ever went hunting for roe deer again. Nor did anyone raise a gun against the wild goats which at times came nearby at the break of dawn. When they passed through the shaded grove, they walked with bowed heads and whispered, “There, in its shadow, the roe deer awaits not to be forgotten.”

.” The mountain understood. A year later, when the grass grew tall and green, old Dodë saw another roe deer pause at the very same brook. A different deer, surely — yet it carried the same serenity. A being that asked for nothing, merely that it not be harmed.

Since that day, no one in that village has ever raised the hand against a roe deer. When outsiders come to hunt, the locals tell them the story of The Broken Feast and say: “The roe deer is not meat. It is sacred. If you kill it, you have stepped upon your very self.”

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

From Antiquity to the 20th century

Historical overview of the period

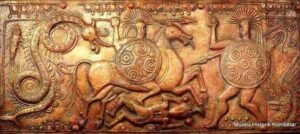

Në traditën shqiptare, veçanërisht në zonat malore dhe rurale ku jeta ishte e lidhur ngushtë me natyrën, ekzistonte një ndjeshmëri e thellë ndaj kafshëve dhe peizazhit përreth. Që nga periudhat parakristiane e deri në fundin e shekullit XX, shqiptarët kanë kultivuar mite dhe zakone që mishërojnë një formë të hershme të ekologjisë kulturore, një respekt për krijesat dhe vendet që konsideroheshin të shenjta. Kafshë të caktuara, si kaprolli, sorkadhja apo dhia, por edhe drurë të mëdhenj që rriteshin pranë mrizeve ku pushonte bagëtia, përfaqësonin simbole të paprekshme, të shenjta, e të lidhura me botën hyjnore ose me fatin e komunitetit.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

Shoqëria tradicionale shqiptare, e vendosur përballë sfidave të mbijetesës në një mjedis të egër por të pasur natyror, ndërtoi një sistem simbolik dhe normativ që shërbente si mburojë për ruajtjen e ekuilibrit natyror. Përtej funksionit mitik dhe fetar, këto ndalesa dhe besëtytni shërbenin edhe si mekanizma për të ruajtur burimet e jetesës: ujërat, pyjet, bagëtinë dhe kafshët e egra. Ndalohej vrasja e disa kafshëve, si kaprolli, për shkak të hijeshisë dhe sjelljes së qetë dhe të pafajshme, ndërsa dhitë e egra apo sorkadhja ruheshin si mbartëse të begatisë dhe pjellorisë. Po kështu, në mrize, pra ato zona të qeta dhe me hije ku bagëtia pushonte gjatë verës, nuk duhej bërë zhurmë, nuk duhej therur bagëti dhe as të priteshin drurët që i hijeshonin këto vende. Këto ishin jo vetëm zona të shenjta, por edhe ekologjikisht të domosdoshme për ciklin jetësor të barinjve dhe gjësë së gjallë.

Tregimi “Gjahu i Malësorëve” i Kostandin Kristoforidhit është një nga rrëfimet më prekëse që shpjegon këtë marrëdhënie mes njeriut dhe natyrës. Në të, një grup malësorësh niset për gjueti dhe pas shumë përpjekjesh, arrin të vrasë një kaproll. Gëzimi i zakonshëm i gjuetisë zbehet menjëherë kur njëri nga gjahtarët afrohet dhe sheh që kaprolli, i plagosur, "qan si njeri". Kjo skenë e mbushur me dhimbje kthehet në një kthesë morale për gjahtarin, i cili shprehet i penduar, duke thënë: “Më mirë të mos e kisha vrarë.” Ky moment është një apel i fortë etik dhe filozofik, që ndan botën e instinktit nga ajo e ndërgjegjes. Kaprolli këtu nuk është më një gjah, por një qenie me ndjeshmëri, e shenjtëruar nga vetë forca e dhimbjes që shfaq. Kristoforidhi, përmes këtij rrëfimi, na lë trashëgimi një mit të fuqishëm për çdo kohë: natyra, nëse nuk trajtohet me respekt, shndërrohet në burim vuajtjeje fizike e shpirtërore për vetë njeriun.

Veç kaprollit, në zonat malore të Shqipërisë ekzistonin edhe tabu të tjera që ndalonin vrasjen e dhisë së egër apo sorkadhes, veçanërisht kur ato shfaqeshin vetëm pranë fshatit apo ishin shtatzëna. Njerëzit e kohës besonin në fuqinë mbrojtëse e shëruese të këtyre kafshëve. Po ashtu në zonën e Mirditës, etnologu Mark Tirta rrëfen për drurët e mëdhenj që rriteshin në mrize që kishin një status mistik, e prandaj në to s’mund të bëhej dru zjarri, nuk duhej të dëmtoheshin e madje ndonjëherë u ofroheshin flijime simbolike.

Këto rregulla zakonore, ndonëse nuk përmendin drejtpërdrejtë kaprollin, bartin ide të ngjashme mbi kufijtë e sjelljes së lejuar ndaj natyrës. Shenjtërimi i drurëve apo i kafshëve ishte në thelb një kod ekologjik i transmetuar gojarisht.

Message

Miti i shenjtërisë së kaprollit dhe tregimet popullore na kujtojnë se njeriu nuk është zot mbi natyrën, por pjesë e saj. Vrasja e kaprollit, në vend që të sjellë triumf, sjell pendim. Ky është një mësim i thellë moral që thekson nevojën për ndjeshmëri, respekt dhe vetëpërmbajtje në raport me natyrën. Kjo trashëgimi kulturore përçon vlera të rëndësishme për marrëdhënien tonë me ambientin, ku mbrojtja e një kafshe ose e një druri është një akt që mbron edhe ekuilibrin e brendshëm të njeriut.

Meaning in Today’s Context

In today’s world, when nature has become an object of destruction by human hands, when parks are demolished to make way for buildings, when forests disappear and burn due to negligence, when animal habitats are damaged and destroyed — this story reminds us that animals are not only beings with souls, but also sacred creatures. Animals do not seek revenge, yet a person can never find peace after killing an innocent being. Today, just as centuries ago, this story carries the same message: nature is sacred and must be protected.

Bibliography

- Kristoforidhi, Kostandin. Gjahu i Malësorëve, Ndërmarrja Shtetnore e Botimeve dhe Shpërndarjes, Tiranë 1950.

- Tirta, Mark. Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, Tiranë, 2004.

- Gjeçovi, Shtjefën. Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, botimi i përpunuar. Tiranë: Argeta LMG, 2001