Event

In the village of Mushtë, in the region of Mirdita, legend tells of a young Dragon born into a humble family of shepherds. Though seemingly an ordinary child, from an early age he showed signs of the extraordinary: he laughed only when the rain poured down, moved stones that grown men could not lift, and always slept with his face turned towards the mountain.

When the Kulshedra awoke from the caves of Gomsiqe and began to devour the clouds — unleashing lightning storms and hail upon the crops of Orosh — the villagers gathered in fear and counsel. An old man, wise in the ways of the ancestors, said, “The time has come. The Dragon will know on his own when the moment arrives.” And verily it so happened. During one night when the sky grew darker than ever it had ever before, the Dragon climbed the mountain facing the cave and called the Kulshedra by name.“

“Do not destroy the land of my people!” he cried.

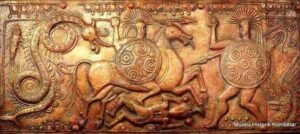

The Kulshedra emerged — swollen, her hair dragging the clouds, her tongues of fire swallowing the darkness. She hurled storms, but the Dragon stood his ground, leaning upon a heavy plowshare, which he wielded as a spear. In the final moment, the legend says, lightning split the sky and struck the Kulshedra — the Dragon’s hand guiding the bolt toward her lair thus sealing her doom.

In Mushtë, they say that on a sharp cliff above the valley, one can still see “the Dragon’s Footprint”, a strange mark shaped to the likeness of a human foot. In Gomsiqe, there is “the Dragon’s Stone”, the place where he rested for the last time before setting out on his eternal battle.

In other parts of northern Albania (especially in Pukë and Tropojë) the Dragon may appear as a bird or a ram with wings of fire, while the Kulshedra may take the form of a woman hiding among rocks or underground springs. In Dibra e Madhe, people say the Kulshedra is a woman with long braids who appears before great floods and vanishes the moment the Dragon rises upon the trembling oaks, heralding the storm’s end.

Scholars have compared these legends to Indo-European mythical models of “the hero who slays the monster,” noting that the Albanian version preserves more archaic pagan elements, especially in Mirdita, where the oral accounts remain rich, complete and less influenced by later reinterpretations.

When the Kulshedra awoke from the caves of Gomsiqe and began to devour the clouds — unleashing lightning storms and hail upon the crops of Orosh — the villagers gathered in fear and counsel. An old man, wise in the ways of the ancestors, said, “The time has come. The Dragon will know on his own when the moment arrives.” And verily it so happened. During one night when the sky grew darker than ever it had ever before, the Dragon climbed the mountain facing the cave and called the Kulshedra by name.“

“Do not destroy the land of my people!” he cried.

The Kulshedra emerged — swollen, her hair dragging the clouds, her tongues of fire swallowing the darkness. She hurled storms, but the Dragon stood his ground, leaning upon a heavy plowshare, which he wielded as a spear. In the final moment, the legend says, lightning split the sky and struck the Kulshedra — the Dragon’s hand guiding the bolt toward her lair thus sealing her doom.

In Mushtë, they say that on a sharp cliff above the valley, one can still see “the Dragon’s Footprint”, a strange mark shaped to the likeness of a human foot. In Gomsiqe, there is “the Dragon’s Stone”, the place where he rested for the last time before setting out on his eternal battle.

In other parts of northern Albania (especially in Pukë and Tropojë) the Dragon may appear as a bird or a ram with wings of fire, while the Kulshedra may take the form of a woman hiding among rocks or underground springs. In Dibra e Madhe, people say the Kulshedra is a woman with long braids who appears before great floods and vanishes the moment the Dragon rises upon the trembling oaks, heralding the storm’s end.

Scholars have compared these legends to Indo-European mythical models of “the hero who slays the monster,” noting that the Albanian version preserves more archaic pagan elements, especially in Mirdita, where the oral accounts remain rich, complete and less influenced by later reinterpretations.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

From pre-Christian times through the 20th century, rooted in the mythological worldview of ancient Albanian pagan beliefs.

Historical overview of the period

In the oral tradition of Mirdita and other northern regions, profound mythological narratives have survived from an ancient world where nature represented not a mere a background to life, but a moving power and oftentimes threatening. Two figures embody this worldview more than any others – the Kulshedra and the Dragon. These opposing mythical beings symbolize the fundamental duality of existence: destructive evil versus protective good. The Kulshedra, a fierce and voracious creature, brings storms, hail, floods and landslides, endangering human life and livelihood. Opposite her stands the Dragon — the mythical hero, usually a male figure, who rises to defend life, the land and natural order.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

The harsh mountain terrain, the struggle for survival amid extreme climates and human’s total dependence on the forces of nature transformed myth into a vital form of explanation and solace. In these circumstances, the people of northern Albania imagined the world’s conflicts — storms, floods, earthquakes — as the workings of the Kulshedra, a being of cursed and supernatural powers. Against this destructive force, they envisioned a protector — the Dragon — a being not always divine but born among humans, taking the form of a child, a man, a bird or else a ram, endowed with extraordinary powers by nature itself. He became the embodiment of justice, representing hope and the courage to confront evil.

Message

The battle between the Dragon and the Kulshedra stands as an metaphor for the eternal struggle between good and evil, between the community’s protective strength and the forces of destruction stemming from nature or coming from the outside world. This mythology taught that evil is never invincible and that it can be faced through courage, sacrifice and connection to the land and community. Today, the legends of the Dragon and the Kulshedra are not mere echoes of the past, but a living heritage carrying deep cultural and educational values. They help reinforce local identity and inspire appreciation for Albanian mythology, while also promoting cultural tourism, especially in regions like Mirdita, where such legends live on through toponyms, folklore and collective memory.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Today, the tales of the Dragon and the Kulshedra are not merely memories of a bygone era, but part of a living heritage that carries cultural and educational value. They can be used to strengthen the sense of local identity, to inspire appreciation for Albanian mythology, and to promote cultural tourism — especially in regions like Mirdita, where the legends are embodied in place names and collective memory.

Bibliography

- Tirta, Mark. Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë [Mythology among the Albanians]. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, Tiranë, 2004.

- Tirta, Mark. Panteoni e simbolika, doke e kode në etnokulturën shqiptare [Pantheon and symbolism, customs and codes in Albanian ethnoculture]. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, Tiranë, 2007.