Event

Celebrations in the small villa at the outskirts of Rome was reserved to only a few guests: two wine merchants from the Illyrian lands and Titus Aelius Varro, a soldier with silvered hair and deep, probing eyes. He had served for many years as a centurion across various provinces of the Empire.

At the host’s signal, abundant food and drink were served. When he learned that the guests came from the Illyrian regions, Titus immediately joined their conversation. Whenever he heard the word Illyria, something stirred within him… a pulse, a longing that no discipline could suppress... Slowly, his heart seemed to swell, ready to burst from his chest.

— From which land do you come? he asked, trying to steady his voice.

The younger merchant, a man with sharp eyes and a thick beard, smiled.

— From Dyrrachium. We have just brought to market our finest wine — we call it Balisca.

The servant lifted the amphora onto his shoulder. Titus’s gaze fixed on the seal that hung from the vessel’s neck, a small mark of vine leaves encircling the letter D, the monogram of Dyrrachium. He knew that symbol all too well. His face turned pale. A distant memory rising like a tide and engulfing him… an image from a past that could not turn back... As he drank the first sip of wine, her silhouette appeared before him and he heard again the echo of her laughter.

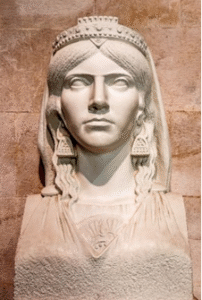

Titus had met Diona during a months-long posting near Dyrrachium. One summer day, while searching for the road to camp, his eyes caught sight of her… a beautiful young woman tending the family vineyards, renowned as the finest in the region. Her father was the most skilled producer of balisca wine, a craft passed down through generations and guarded with sacred devotion. For the vintners of Dyrrachium, balisca was more than a drink. It was a living bond with the past, with the soil that nourished their people and the deities who blessed the harvest.

Music had begun at the Roman feast. Courtesans and dancers filled the hall. Titus’s thoughts drifted back to the first celebration he had attended among the Illyrians.

— You are a strange people, he told the merchants, who seemed unaccustomed to Roman excess. In your feasts, women take part as men do — they speak freely and drink among them.

The merchants smiled, their eyes carrying a quiet reverence for their homeland’s customs.

— In our village, said the elder merchant, women are the heart of every feast. They care for the vineyards, the wine and the stories they tell so beautifully. Without them, a feast would be but an ordinary day.

— You Illyrians eat seated and know how to celebrate until dawn, yet never lose yourselves to drink as others do. How do you know when to stop?

The two men exchanged a knowing glance. The younger lifted the edge of his cloak and showed the belt tied around his waist.

— It is our tradition to restrain ourselves by tightening the belt...

Titus smiled faintly. As he drank more of the sweet wine, the vision of Diona grew clearer. He longed to be there again, in the heart of Illyria, beside Diona with her wavy hair and crystal skin, amidst the green vineyards, the scent of new wine and songs rising towards the sky.

He wished he could leave war behind and go on living with her by the sea, waking each morning to the music of the waves. That night, he did not wish to lose her image. Rising from the table, he took the amphora in his arms and withdrew, wrapped in the warmth of reminiscences. He approached the window and it seemed to him that across the sea… he glimpsed that Illyrian girl once more… brought back to life by this blessed sweet wine. How he wished that night that balisca would never end...

At the host’s signal, abundant food and drink were served. When he learned that the guests came from the Illyrian regions, Titus immediately joined their conversation. Whenever he heard the word Illyria, something stirred within him… a pulse, a longing that no discipline could suppress... Slowly, his heart seemed to swell, ready to burst from his chest.

— From which land do you come? he asked, trying to steady his voice.

The younger merchant, a man with sharp eyes and a thick beard, smiled.

— From Dyrrachium. We have just brought to market our finest wine — we call it Balisca.

The servant lifted the amphora onto his shoulder. Titus’s gaze fixed on the seal that hung from the vessel’s neck, a small mark of vine leaves encircling the letter D, the monogram of Dyrrachium. He knew that symbol all too well. His face turned pale. A distant memory rising like a tide and engulfing him… an image from a past that could not turn back... As he drank the first sip of wine, her silhouette appeared before him and he heard again the echo of her laughter.

Titus had met Diona during a months-long posting near Dyrrachium. One summer day, while searching for the road to camp, his eyes caught sight of her… a beautiful young woman tending the family vineyards, renowned as the finest in the region. Her father was the most skilled producer of balisca wine, a craft passed down through generations and guarded with sacred devotion. For the vintners of Dyrrachium, balisca was more than a drink. It was a living bond with the past, with the soil that nourished their people and the deities who blessed the harvest.

Music had begun at the Roman feast. Courtesans and dancers filled the hall. Titus’s thoughts drifted back to the first celebration he had attended among the Illyrians.

— You are a strange people, he told the merchants, who seemed unaccustomed to Roman excess. In your feasts, women take part as men do — they speak freely and drink among them.

The merchants smiled, their eyes carrying a quiet reverence for their homeland’s customs.

— In our village, said the elder merchant, women are the heart of every feast. They care for the vineyards, the wine and the stories they tell so beautifully. Without them, a feast would be but an ordinary day.

— You Illyrians eat seated and know how to celebrate until dawn, yet never lose yourselves to drink as others do. How do you know when to stop?

The two men exchanged a knowing glance. The younger lifted the edge of his cloak and showed the belt tied around his waist.

— It is our tradition to restrain ourselves by tightening the belt...

Titus smiled faintly. As he drank more of the sweet wine, the vision of Diona grew clearer. He longed to be there again, in the heart of Illyria, beside Diona with her wavy hair and crystal skin, amidst the green vineyards, the scent of new wine and songs rising towards the sky.

He wished he could leave war behind and go on living with her by the sea, waking each morning to the music of the waves. That night, he did not wish to lose her image. Rising from the table, he took the amphora in his arms and withdrew, wrapped in the warmth of reminiscences. He approached the window and it seemed to him that across the sea… he glimpsed that Illyrian girl once more… brought back to life by this blessed sweet wine. How he wished that night that balisca would never end...

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

From the late 4th century BCE to the 1st century CE

Historical overview of the period

For Illyrians wine represented a distinctive element of both material and spiritual heritage, encompassing not only viticulture and production (notwithstanding its modest in scale) but also the social, regal and religious dimensions of its consumption. Archaeological evidence for wine use dates back to as early as the 6th century BCE. Contact with Greeks and Romans deepened the tradition, making wine a symbol of both sacred offerings and social communion — consumed during communal festivities, feasts dedicated to deities and council gatherings.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

Alongside the numerous archaeological finds related to wine transport (amphorae), mixing vessels and fine tableware, historical sources also document local Illyrian wine production. Aristotle (832a.22) mentions a honey-based wine produced by the Illyrians known as the Taulantii, made from honeycombs — a strong and very sweet drink. Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia XIV.2) records that the most celebrated Illyrian wine was the Balisca, produced from the Balisk grape variety cultivated around Dyrrachium. It was exported to Rome before the Augustan period and aged remarkably well. Some scholars even suggest that the vineyards of Bordeaux may trace their lineage to this Dyrrachian variety. Ancient sources such as Theopompus (FGrH 115 F 38, ap. Athenaeus 11.476d) describe Illyrian banquets, noting their distinctive traits by comparison to Greek and Roman customs.

Message

This story emphasizes respect for cultural traditions while articulating universal human dimensions transcending cultural or ethnic boundaries, encompassing pure feelings, memories and the sense of belonging. By way of contrasts, it highlights wisdom in moderation and the balance between joy and self-restraint — between sensibility and devotion.

Meaning in Today’s Context

The episode transcends cultural borders, suggesting that essential human values and experiences — love, memory, care for others and harmony with nature — are universal and surpass both geography and time. Through the figure of the Illyrian maiden, depicted as a pure vision and an ideal of love and nature, the narrative invites reflection on what truly endures in human condition: the sense of belonging, peace and living memories which permeate through a people’s traditions.

Bibliography

- Étienne, Roland, “L’origine épirote du vin de Bordeaux antique,” in P. Cabanes (ed.), L’Illyrie méridionale et l’Épire dans l’Antiquité: Actes du colloque international de Clermont-Ferrand (22–25 octobre 1984), Clermont-Ferrand, 1987, pp. 239–243.

- Lahi, Bashkim, “Kultura e verës si rafinesë në kulturën qytetare ilire – rasti i Lissos” [“The culture of wine as refinement in Illyrian urban culture – the case of Lissus”], Iliria 36 (2012), pp. 173–185.

- Shpuza, Saimir, “Importi dhe prodhimi i verës dhe vajit në Ilirinë e Jugut” [“Import and production of wine and oil in Southern Illyria”], Iliria 33 (2007), pp. 219–232.