Event

I am Dardani, scribe of sacred manuscripts and keeper of stories not written in books but in stone — for the eyes of those who can read without words. That morning, I learned a truth never spoken aloud: “The stone laid at the foundation of faith speaks louder than any decree.”

After the earthquake that had toppled walls and altars, the dust of the old world was being replaced by new stone. Emperor Justinian, proud of his Dardanian roots, had ordered the city’s reconstruction and granted it a new name — Iustiniana Secunda. It was more than a rebuilding: it was an act of remembrance and power, a declaration that Dardanian blood had not perished but was rising anew — in fresh stone and mosaics glistening beneath the Balkan sun.

Amid the newly raised buildings stood the great basilica, within which a rare mosaic was to be laid, crafted with care and mastery. Each small stone was chosen one by one from the city’s quarries, built upon the ruins of the old, as if rooting itself in the very foundations of faith the strength flowing from the past.

Heeeej URBEM DARDANIAE, o heeeej (in the city of Dardania)...

On that cold spring morning, as the scent of freshly laid mortar still filled the air, Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora made a decision that surprised many. Instead of gathering the people in a public square, as tradition dictated for proclamations of this kind, they chose to enter the newly built basilica in silence, away from the noise of the crowd. It was not merely a place for prayer and the dedication made that day was not directed toward divine worship: it was a symbolic act, charged with legal and spiritual significance alike.

In a shadowed corner of the basilica, Theodora bowed her head while Justinian spoke softly but with firmness. It was more than a speech. It was an affirmation of the new order being established. That moment, more than any grand ceremony could, bore witness to an epochal transformation. They had chosen the building by not perchance. It was the most visible, the most talked-about in the new city and, precisely for that reason, it became the chosen site for an act profoundly political. Their declaration, though uttered away from the crowd, was more public than any proclamation in the square. It marked a turning point in the relationship between the Church, the Empire and the cities themselves. And it was never forgotten — not by the bishops, not by the citizens, not by history.

Heeeej URBEM DARDANIAE, o heeeej (in the city of Dardania).

After the earthquake that had toppled walls and altars, the dust of the old world was being replaced by new stone. Emperor Justinian, proud of his Dardanian roots, had ordered the city’s reconstruction and granted it a new name — Iustiniana Secunda. It was more than a rebuilding: it was an act of remembrance and power, a declaration that Dardanian blood had not perished but was rising anew — in fresh stone and mosaics glistening beneath the Balkan sun.

Amid the newly raised buildings stood the great basilica, within which a rare mosaic was to be laid, crafted with care and mastery. Each small stone was chosen one by one from the city’s quarries, built upon the ruins of the old, as if rooting itself in the very foundations of faith the strength flowing from the past.

Heeeej URBEM DARDANIAE, o heeeej (in the city of Dardania)...

On that cold spring morning, as the scent of freshly laid mortar still filled the air, Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora made a decision that surprised many. Instead of gathering the people in a public square, as tradition dictated for proclamations of this kind, they chose to enter the newly built basilica in silence, away from the noise of the crowd. It was not merely a place for prayer and the dedication made that day was not directed toward divine worship: it was a symbolic act, charged with legal and spiritual significance alike.

In a shadowed corner of the basilica, Theodora bowed her head while Justinian spoke softly but with firmness. It was more than a speech. It was an affirmation of the new order being established. That moment, more than any grand ceremony could, bore witness to an epochal transformation. They had chosen the building by not perchance. It was the most visible, the most talked-about in the new city and, precisely for that reason, it became the chosen site for an act profoundly political. Their declaration, though uttered away from the crowd, was more public than any proclamation in the square. It marked a turning point in the relationship between the Church, the Empire and the cities themselves. And it was never forgotten — not by the bishops, not by the citizens, not by history.

Heeeej URBEM DARDANIAE, o heeeej (in the city of Dardania).

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

6th century CE

Historical overview of the period

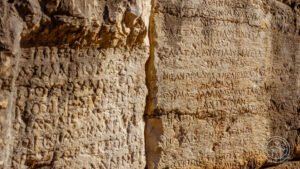

Ulpiana lies near the village of Graçanica, southeast of Prishtina (Kosovo), in a strategic position along major ancient routes connecting Dardania with other Roman provinces. The city was founded in the 2nd century CE, during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117), and took its name Municipium Ulpiana from his family name, Ulpius. Between the 2nd and 4th centuries it flourished economically, becoming one of the most important cities of Roman Dardania. Emperor Justinian I (482–565), himself of Dardanian origin — from the territory of present-day Kosovo — rebuilt the city after a devastating earthquake in the 5th century CE, renaming it Iustiniana Secunda.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

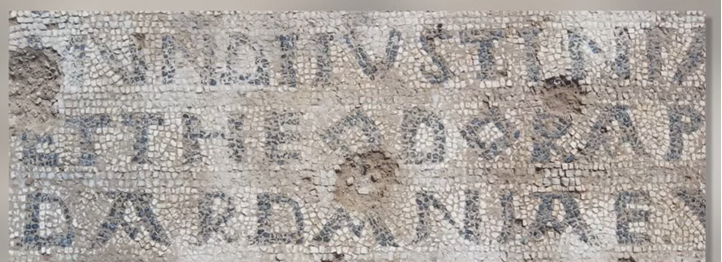

According to Procopius of Caesarea (De Aedificiis, IV, 1, 28–30): “...Among the Dardanians there existed from ancient times a city called Ulpiana. Its surrounding walls had suffered great damage and lost their function, so much of them had to be demolished. Justinian carried out many improvements in this city, giving it the fine appearance it enjoys today; he named it Iustiniana Secunda.” A significant archaeological discovery made in the summer of 2023 relates to an inscription of Emperor Justinian I and Empress Theodora, found in the mosaic of a large late-antique church built under Justinian’s reign. The Latin text bears the dedication urbs Dardaniae — “city of Dardania.” It is one of the rarest imperial dedications known in the Latin world of Late Antiquity.

Message

The significance of this discovery for the history of ancient Dardania and modern Kosovo is multidimensional: it attests to Emperor Justinian’s direct connection to his homeland. The Latin inscription confirms that Justinian himself personally initiated the founding of Iustiniana Secunda. The act simultaneously expresses pride in local origins and a reaffirmation of identity within the empire’s vast framework. ts importance is also political: the dedication is not religious and represents the first known dedication to a city rather than to divinity. It constitutes a political decision enacted within a sacred space, shedding light on how, under Justinian’s rule, the role of the Church evolved into a distinctly political sphere.

Meaning in Today’s Context

In today’s context, great historical works are more than just physical projects; they represent signs of hope, dedication, and unity. This message invites us to reflect on the fact that our actions, even the silent ones, can have a broad impact and endure for generations. In modern terms, this discovery and what it represents testifies to the need for careful and meaningful reconstruction, the importance of cooperation and respect for our identity, as well as the power that our symbols and actions hold in building a better future.

Bibliography

- Goddard, Christophe et al., Ulpiana and Late Antique Dardania: Archaeological Investigations and the Rebuilding under Justinian, Studies in Balkan Archaeology, 2021.

- Hajdari, Arben; Goddard, Christophe; Berisha, Milot, Une nouvelle dédicace de fondation de Justinien et de Théodora à Iustiniana Secunda (Ulpinana, Graçanica, Kosovo), Antiquité Tardive 32 (2024), pp. 183–208.

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta, Ulpiana (Dardania) in Late Antiquity, Late Antique Archaeology, 2010.