Event

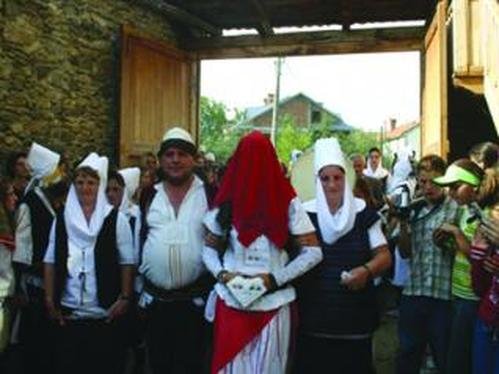

On a quiet summer morning, the village roads stirred with unusual liveliness. The elder men of the clan, dressed in traditional attire, gathered one after another, forming what looked like a solemn procession. At the head of the group stood the “kryekrushk” (the chief escort), usually an older, experienced man who knew the customs and proper honoring of both families. He took the lead for the procession, as also the enunciating of words, greetings and gestures that marked that special day.

Among the greenery and weathered stones which had witnessed generations pass by, the path of the wedding escorts began, not as a simple journey to bring a bride to her new home, but as a sacred passage, a ritual flowing from within the heart of Albanian tradition. The krushqit (wedding escorts) did not travel in silence. They sang. Their song rose into the air, interwoven with the sounds of the çifteli and the echo of flutes. In their hands they carried decorated rifles, not out of fear, but by custom, for no escort was to travel unarmed. Elders told how, in earlier times, an enemy might try to block the procession and dishonor the family of the groom. Thus, the krushqit were not only singers, they were guardians of family honor.

The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, the traditional Albanian customary code, detailed the obligations and courtesies owed to the wedding procession. The krushqit made several stops along the way, not for rest, but for spiritual pauses. At one large stone, the kryekrushk poured a drop of wine and placed a coin upon the earth. All fell silent as he murmured: “For the good fortune of the couple. For a smooth journey. For a long life.” Some lifted their eyes toward the sky, while others raised a toast. Everyone knew this was more than a wedding — it was an alliance, a joining of two families, two houses, two stories into one. And none of it could happen without that sacred road leading.

At the bride’s house, everything breathed reverence. Her mother had not slept all night. She had embroidered by hand the final veil, the token at the same time of pain and blessing. The bride stood there in silence, eyes lowered but face glowing with emotion.

The neighborhood girls sang softly in chorus a song that was both prayer and farewell: “Do not weep, bride, do not shed tears, for with flowers you enter the world…”

When the procession arrived, the bride’s father stood quiet, dignified. All awaited the first words of the kryekrushk. He knocked at the door, then spoke firmly: “We have come to take your daughter — not to take her away, but to make her one of ours. With honor and with faith, as our custom commands.”

The door opened. The bride, veiled in white, stepped forth amid flowers, tears, and blessings. Her mother placed salted bread in her hand and touched her forehead with a drop of water so she would never forget where she came from. The traditional song “Krushqit po shkojnë me lule” (The wedding escorts go forth with flowers) accompanied the procession. Its verses blended joy with melancholy, praising the bride’s beauty and the family’s pride, while also singing out the bittersweet pain of parting. It was an emotional bridge between two homes, a reminder that marriage was both a loss and a union.

The journey of return was quieter. The escorts no longer sang with the same rhythm. Now the sense of responsibility was deeper: they were bringing home a new life, a new honor.

At a spring midway, they stopped again. They sprinkled a few drops of water upon the bride’s eyes. An elder murmured: “So her eyes may always see goodness — and her heart may always feel kindness.”

When they reached the groom’s house, gunshots were fired into the air and the great celebration began. Yet no one forgot that the journey they had made was more than a road — it was a spiritual passage, a ritual of deep symbolism, discipline and emotion.

Among the greenery and weathered stones which had witnessed generations pass by, the path of the wedding escorts began, not as a simple journey to bring a bride to her new home, but as a sacred passage, a ritual flowing from within the heart of Albanian tradition. The krushqit (wedding escorts) did not travel in silence. They sang. Their song rose into the air, interwoven with the sounds of the çifteli and the echo of flutes. In their hands they carried decorated rifles, not out of fear, but by custom, for no escort was to travel unarmed. Elders told how, in earlier times, an enemy might try to block the procession and dishonor the family of the groom. Thus, the krushqit were not only singers, they were guardians of family honor.

The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, the traditional Albanian customary code, detailed the obligations and courtesies owed to the wedding procession. The krushqit made several stops along the way, not for rest, but for spiritual pauses. At one large stone, the kryekrushk poured a drop of wine and placed a coin upon the earth. All fell silent as he murmured: “For the good fortune of the couple. For a smooth journey. For a long life.” Some lifted their eyes toward the sky, while others raised a toast. Everyone knew this was more than a wedding — it was an alliance, a joining of two families, two houses, two stories into one. And none of it could happen without that sacred road leading.

At the bride’s house, everything breathed reverence. Her mother had not slept all night. She had embroidered by hand the final veil, the token at the same time of pain and blessing. The bride stood there in silence, eyes lowered but face glowing with emotion.

The neighborhood girls sang softly in chorus a song that was both prayer and farewell: “Do not weep, bride, do not shed tears, for with flowers you enter the world…”

When the procession arrived, the bride’s father stood quiet, dignified. All awaited the first words of the kryekrushk. He knocked at the door, then spoke firmly: “We have come to take your daughter — not to take her away, but to make her one of ours. With honor and with faith, as our custom commands.”

The door opened. The bride, veiled in white, stepped forth amid flowers, tears, and blessings. Her mother placed salted bread in her hand and touched her forehead with a drop of water so she would never forget where she came from. The traditional song “Krushqit po shkojnë me lule” (The wedding escorts go forth with flowers) accompanied the procession. Its verses blended joy with melancholy, praising the bride’s beauty and the family’s pride, while also singing out the bittersweet pain of parting. It was an emotional bridge between two homes, a reminder that marriage was both a loss and a union.

The journey of return was quieter. The escorts no longer sang with the same rhythm. Now the sense of responsibility was deeper: they were bringing home a new life, a new honor.

At a spring midway, they stopped again. They sprinkled a few drops of water upon the bride’s eyes. An elder murmured: “So her eyes may always see goodness — and her heart may always feel kindness.”

When they reached the groom’s house, gunshots were fired into the air and the great celebration began. Yet no one forgot that the journey they had made was more than a road — it was a spiritual passage, a ritual of deep symbolism, discipline and emotion.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

From the Middle Ages to the 20th century

Historical overview of the period

Marriage in traditional Albanian society represented far more than the union of two individuals. It was an act that defined relations between families, clans and communities. Marriage was tightly bound to the concepts of honor, alliance and social standing.

The ceremony of taking the bride — the “udha e krushqve” (path of the wedding escorts) — embodied symbolically the woman’s transition from her parental home to her husband’s household. Every stage of the journey carried ritual meaning, codified over centuries and charged with spiritual and communal value.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

In rural and highland Albania, marriages were usually arranged between families, mediated by the krushq, respected men who acted as negotiators and representatives of the groom’s family. The journey to fetch the bride thus became a solemn and sacred procession, accompanied by symbolic acts of singing, dance, toasts, rifle salutes and ritual stops at chosen landmarks. These practices combined elements of ancient pagan beliefs, Christian blessing rites, and local customary law, fusing them into a living heritage that defined the moral and cultural landscape of Albanian life.

Message

The “Udha e krushqve” was never just a road itinerary — it was a rite of passage, a living reflection of the Albanian values of honor, unity, dignity and collective memory. Along this sacred road, men and women, the young and the old, carried with them the very essence of a people who celebrated life through ritual. Even today, though the horse caravans have been replaced by car processions and wedding horns, the spirit enlivening that ancient path still endures. When Albanian cities echo with joyful wedding convoys, it is the voice of that road that revisits — reminding us that marriage, at its heart, is not merely a civil act, but a sacred union grounded in values, custom and emotion.

Meaning in Today’s Context

In today’s world, the ritual of the wedding procession carries an important message — that a wedding is not merely the union of two young people, but a strong bond between families, a symbol of friendship, community spirit, trust, and honor. This foundation gives marriage its strength, making the family institution sacred. The wedding guests (the “krushq”) also serve as guarantors of the new family’s longevity. At a time when families are breaking apart and divorces are increasing, the messages carried by the path of the “Krushq” remain powerful lessons to remember and pass on.

Bibliography

- Dibra, Miaser. Ceremoniali i dasmës në qytetin e Shkodrës [The wedding ceremonial in the city of Shkodra]. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave, 2004.

- Velianj, Albana. Rite e simbole në dasmën tradicionale shqiptare [Rites and symbols in the traditional Albanian wedding]. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave, 2017.

- Gjeçovi, Shtjefën. Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit [The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini]. Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese Kuvendi, 2001.