Event

The sun was setting over the Strait of Korkyra, casting a golden light upon the white stones of the Sanctuary of Asclepius. The city that had echoed all day with the shouts of sailors and calls of merchants and artisans, was slowly settling into its well-earned evening calm.

Within the sacred enclosure, among ancient oaks and the stone wall that separated the everyday world from the divine, a small group of people had gathered. Among them, Argeia, a woman of mature years, walked with steady steps. She had long awaited this moment. Widowed at a young age, she had inherited a considerable estate from her merchant family, which she had managed with wisdom and dignity, earning the respect of the citizens of Buthrotum. The act she was about to undertake was anything but ordinary. In Butrint, women like her — widows or heiresses who owned slaves — had begun, in ways unusual for their time, to take part in public life. Some among them had chosen to grant freedom to their slaves.

That day, in the presence of Asclepius, Zeus, and her fellow citizens, Argeia freed four slaves — all diligent workers, skilled women housekeepers, and skilled artisans. Among them was a young man named Derdas, who had been part of her household since childhood. When Argeia’s brother fell ill, Derdas cared for him during three long years. During those sleepless nights of fever, he prayed in silence to Asclepius and lit torches at the altar for his healing. And the healing came slowly, but surely… just like Argeia’s decision to reward him not only with freedom but so with gratitude.

“In my name, you are no longer property, she said. You are a free man before the eyes of Zeus Soter (the Deliverer).”

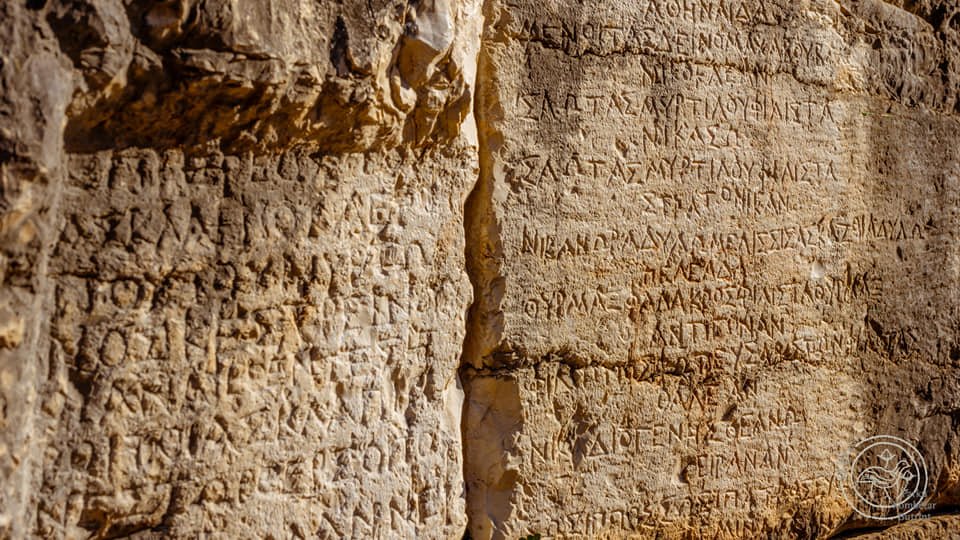

Her words were carved in stone, like hundreds of other acts of manumission that already adorned the walls of the theater, the entrances of temples and the sacred paths of Buthrotum. Yet something set this inscription apart from the rest: it bore the engraved name of a woman with no male co-signer, which is to say no accompanying man’s name to guarantee the act of freeing from the bondage of slavery. The inscription stood as clear testimony to its time and place: Buthrotum as a city, unlike many other cities of the ancient world, whereby women were granted not only with voice but also a place in history.

In the temple of Asclepius, the scent of incense rose curling through the air. Argeia knelt and placed a golden coin upon the altar. As she prayed for the freedom and health of her former servants, she glimpsed the vision of the little girl she once was, watching the men of her city inscribe history upon stone. Today, she wrote her own, alone, without a man at her side. Buthrotum, city of the gods and guardian of freedom won with dignity, now bore her name engraved in stone — for the generations yet to come.

Within the sacred enclosure, among ancient oaks and the stone wall that separated the everyday world from the divine, a small group of people had gathered. Among them, Argeia, a woman of mature years, walked with steady steps. She had long awaited this moment. Widowed at a young age, she had inherited a considerable estate from her merchant family, which she had managed with wisdom and dignity, earning the respect of the citizens of Buthrotum. The act she was about to undertake was anything but ordinary. In Butrint, women like her — widows or heiresses who owned slaves — had begun, in ways unusual for their time, to take part in public life. Some among them had chosen to grant freedom to their slaves.

That day, in the presence of Asclepius, Zeus, and her fellow citizens, Argeia freed four slaves — all diligent workers, skilled women housekeepers, and skilled artisans. Among them was a young man named Derdas, who had been part of her household since childhood. When Argeia’s brother fell ill, Derdas cared for him during three long years. During those sleepless nights of fever, he prayed in silence to Asclepius and lit torches at the altar for his healing. And the healing came slowly, but surely… just like Argeia’s decision to reward him not only with freedom but so with gratitude.

“In my name, you are no longer property, she said. You are a free man before the eyes of Zeus Soter (the Deliverer).”

Her words were carved in stone, like hundreds of other acts of manumission that already adorned the walls of the theater, the entrances of temples and the sacred paths of Buthrotum. Yet something set this inscription apart from the rest: it bore the engraved name of a woman with no male co-signer, which is to say no accompanying man’s name to guarantee the act of freeing from the bondage of slavery. The inscription stood as clear testimony to its time and place: Buthrotum as a city, unlike many other cities of the ancient world, whereby women were granted not only with voice but also a place in history.

In the temple of Asclepius, the scent of incense rose curling through the air. Argeia knelt and placed a golden coin upon the altar. As she prayed for the freedom and health of her former servants, she glimpsed the vision of the little girl she once was, watching the men of her city inscribe history upon stone. Today, she wrote her own, alone, without a man at her side. Buthrotum, city of the gods and guardian of freedom won with dignity, now bore her name engraved in stone — for the generations yet to come.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

3rd–1st century BCE

Historical overview of the period

The ancient city of Bouthrotos (Butrot, Butrint), located at the southern tip of the Ksamil Peninsula, occupied a strategic crossroads along the maritime routes of the Ionian coast. Butrint belonged to the Epirote region of Chaonia and, during the Hellenistic period and later under Roman influence, developed into an important cultural and religious center. During this era, the practice of slave manumission was widely documented in Butrint, carrying public, legal and religious significance. Acts of emancipation were engraved on stone and displayed in public structures such as theaters, sanctuaries, and sacred walls, lending the act a solemn dimension — freedom “before the eyes of the gods.”

Note: The names of the individuals mentioned are recorded in authentic manumission inscriptions from Butrint.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

In ancient Greek and Roman societies, the role of women was generally limited, defined by social and legal frames that placed them at the periphery of public life. Yet the evidence from between the 3rd and 1st centuries BCE reveals a different reality. In this city, 218 inscriptions have been preserved documenting the emancipation of roughly 600 slaves, carried out “in the presence” of protective deities such as Asclepius (highly venerated in Butrint) and Zeus Soter (“the Deliverer”), giving these acts a juridical, religious and civic character. In many of these inscriptions, the central figure is a woman: acting as head of household, administering property, making independent decisions, and signing acts of manumission without the authorization of a male guardian.

These facts reveal a distinctive form of social organization in Butrint — a territory at the frontier of the Greek world and at the threshold of the Roman era — where the role of women was more visible, autonomous and institutionalized than in the classical Greek city-states. The destiny of the freed individuals, too, reflects a heightened awareness of human dignity and social integration, distinguishing Butrint from the more conventional models of antiquity.

Message

The story of Argeia bears witness to the unique status of women in Butrint, contrasting with reference to the place typically assigned to them in Greek societies of the time. In an ancient world where women were often excluded from public and legal life, every act in which a woman exercised her own will — to free a slave, to defend a right, or to influence community life — opens a precious window onto a more complex and gender-balanced reality than is commonly imagined for antiquity.

The right to grant freedom was not merely a humanitarian gesture but a clear expression of moral, economic and legal authority. Within the family sphere, the woman appears as the center of domestic life — educator of generations, guardian of lineage and administrator of the household economy. She could own property, manage it independently, and act as the head of the family, even serving as a valid witness in legal documents. In the religious sphere, women participated actively, often in high offices as priestesses or interpreters of oracles — roles that gave them significant influence in the spiritual and social life of the community. In some cases, this involvement extended to the uppermost levels of political and religious hierarchy.

This reality positions Butrint not only as a major cultural and juridical center but also as a space where the voice of women was heard and valued — offering a different vision of the ancient world: more diverse, more just and profoundly humane.

Meaning in Today’s Context

Aktet e lirimit të skllevërve në Butrint, të nënshkruara nga gra që vepronin me autoritet moral dhe ligjor, hedhin dritë mbi rolin dhe vendin që gruaja ka pasur në historinë e trojeve tona. Këto akte përbëjnë një dëshmi të çmuar të trashëgimisë sonë kulturore, duke treguar se, edhe në periudha të ndikuara fort nga struktura patriarkale, kanë ekzistuar hapësira ku gratë jo vetëm që ishin të pranishme, por edhe vendimmarrëse – të afta të ushtrojnë drejtësi, të mbrojnë dinjitetin dhe të japin liri. Kjo dëshmi historike duhet të na shërbejë si pikë reflektimi dhe nxitje për veprim në të tashmen.

Bibliography

- • Cabanes, Pierre, Vendi i gruas në Epirin antic [The place of women in ancient Epirus], Iliria 13/2 (1983), pp. 193–209.DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/iliri.1983.1833

- Cabanes, Pierre; Drini, Faik, Corpus des inscriptions grecques d’Illyrie méridionale et d’Épire II: Inscriptions de Bouthrotos, Coll. Études épigraphiques 2, Paris, 2007.

- Drini, Faik; Budina, Dhimosten, Mbishkrime të reja të zbuluara në Butrint [New inscriptions discovered in Butrint], Iliria 11/1 (1981), pp. 227–234. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/iliri.1981.1754

- • Drini, Faik, Ilirët dhe epirotët (Paralele dhe veçanti) [The Illyrians and the Epirotes (Parallels and distinctions)], Iliria 19/2 (1989), Proceedings of the Symposium Ilirët dhe Bota Antike / Die Illyrer und die antike Welt, pp. 55–64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/iliri.1989.1537