Event

“Come, children… it’s bedtime!”… “Grandfather, please, tell us once more the story of King Gentius and the magic flower he discovered!”

Along the steep shores of the Lake of the Labeates, among mountains that silently guard the memories of centuries, ruled Gentius — son of Pleuratus and last king of the Illyrians. When he received the crown from his father, the kingdom was surrounded by enemies. Across the Adriatic, the Romans had begun their march, conquering one by one the neighboring lands, like waves striking mercilessly against the coast. But Gentius, proud and unyielding, refused to submit. His army was brave, his fleet formidable. The Liburnian ships, light and swift, cut through the sea like arrows, striking suddenly and leaving behind only the echo of Illyrian valor.

Gentius was a wise ruler who valued knowledge as much as the sword. He loved nature and often told his warriors: “A battle is won first with a clear mind and a healthy body — only then with weapons.”

One day, while walking along a rugged path, he noticed an unusual flower, with petals gleaming like the rays of the sun, growing alone among the rocks. The king knelt to observe it and, at that moment, felt that was no ordinary flower. It was the right one. From its roots, a healing ointment was prepared that miraculously cured the wounds of soldiers in the bloody battles against Rome. Soon its fame spread beyond the Illyrian lands. People called it “The King’s Flower”, but in time, the world came to know it by another name — Gentiana.

After Gentius died in exile and Rome finally conquered Illyria, the Gentiana continued to bloom in the high mountain pastures, where the air is pure and the earth still holds the traces of ancestors. The flower became the king’s gift to the world — a living memory of an age when Illyria stood proud, a symbol of Gentius’s wisdom and love for his land and people. Each time the gentianas blossom and paint the mountain slopes, a soft breeze descends… whispering the still enduring glory of Gentius.

The grandfather rose slowly. With trembling hands, he tucked the children under their blankets. They were already dreaming… brave and warrior-like Liburn sailing under the moonlight, while Gentiana floated from mountain to mountain, healing the wounds of those who fought for their homeland.

Along the steep shores of the Lake of the Labeates, among mountains that silently guard the memories of centuries, ruled Gentius — son of Pleuratus and last king of the Illyrians. When he received the crown from his father, the kingdom was surrounded by enemies. Across the Adriatic, the Romans had begun their march, conquering one by one the neighboring lands, like waves striking mercilessly against the coast. But Gentius, proud and unyielding, refused to submit. His army was brave, his fleet formidable. The Liburnian ships, light and swift, cut through the sea like arrows, striking suddenly and leaving behind only the echo of Illyrian valor.

Gentius was a wise ruler who valued knowledge as much as the sword. He loved nature and often told his warriors: “A battle is won first with a clear mind and a healthy body — only then with weapons.”

One day, while walking along a rugged path, he noticed an unusual flower, with petals gleaming like the rays of the sun, growing alone among the rocks. The king knelt to observe it and, at that moment, felt that was no ordinary flower. It was the right one. From its roots, a healing ointment was prepared that miraculously cured the wounds of soldiers in the bloody battles against Rome. Soon its fame spread beyond the Illyrian lands. People called it “The King’s Flower”, but in time, the world came to know it by another name — Gentiana.

After Gentius died in exile and Rome finally conquered Illyria, the Gentiana continued to bloom in the high mountain pastures, where the air is pure and the earth still holds the traces of ancestors. The flower became the king’s gift to the world — a living memory of an age when Illyria stood proud, a symbol of Gentius’s wisdom and love for his land and people. Each time the gentianas blossom and paint the mountain slopes, a soft breeze descends… whispering the still enduring glory of Gentius.

The grandfather rose slowly. With trembling hands, he tucked the children under their blankets. They were already dreaming… brave and warrior-like Liburn sailing under the moonlight, while Gentiana floated from mountain to mountain, healing the wounds of those who fought for their homeland.

There is no audio content available. Add an audio URL in the admin panel.

There is no video content available. Add a video URL in the admin panel.

Historical period:

2nd century BCE

Historical overview of the period

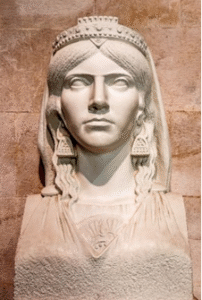

Gentius, son of Pleuratus II, was the last king of the Illyrian kingdom of the Labeates, reigning approximately between 181 and 168 BCE, during one of the most turbulent periods of Illyrian history. At that time, Illyria was caught between two expanding powers, viz. Rome and Macedonia.

King Gentius is remembered for his efforts to preserve Illyrian independence while the Roman Republic was extending its influence across the Balkans. During the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BCE), he allied with Perseus, the king of Macedonia, and declared war on Rome. The alliance failed, and Gentius’s army was defeated by the Romans near Shkodra, the capital of the Labeates.

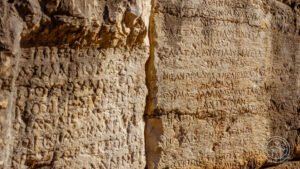

Archaeological evidence from his reign, including coins minted in Shkodra and Lissus (Lezha) bearing his name and portrait, testifies to a flourishing Illyrian state and its sophisticated political and economic organization.

Conditions that gave rise to the event

Written sources highlight King Gentius as a patron of knowledge, science, and particularly medicine and botany. In Naturalis Historia (Book 25.34), Pliny the Elder credits Gentius as the first to identify and use the healing properties of the root of the plant later named Gentiana lutea — the great yellow gentian — in his honor.

Message

King Gentius, the last monarch of the Illyrians, embodies the resistance of an ancient people against the expansion of the Roman Republic — a civilization that would later shape the whole of the Western world. Yet beyond military valor, his story conveys a deeper legacy: a bond between wisdom, nature and resilience. His discovery of the Gentiana plant intertwines history and legend, symbolizing the harmony between human knowledge and the healing power of the earth. In cultural memory, Gentius endures not only as a ruler and warrior but as a guardian of Illyrian wisdom, a timeless reminder that the true strength of a people lies as much in their spirit and knowledge as in their arms.

Meaning in Today’s Context

The figure of Genthi represents one of the clearest expressions of the political and cultural identity of the Illyrians during the final phase of their existence as organized state units. Through him, Albanian history gains a reference point for understanding how belonging was shaped in antiquity—through language, institutions, territory, and spiritual connection to the land. Although we still cannot speak of national consciousness in the modern sense, in Genthi we find a clear awareness of political unity and the common interest of the Illyrians, as well as the threat posed by an expansionist power such as Rome. In this sense, Genthi is a symbol of an Illyrian identity striving to maintain cohesion in the face of assimilation. His connection to nature, support for knowledge, and values of self-determination give this figure a special dimension in Albanian spiritual heritage. Today, he is remembered not only as a historical figure but as an important node in collective memory that helps build a deeper awareness of the roots of Albanian identity and the connection to Illyrian civilization as a fundamental part of the country’s history.

Bibliography

- Islami, Selim. Prerjet monetare të Skodrës, Lisit dhe Gentit [Coin mintings of Scodra, Lissus, and Gentius], Iliria 2 (1972), 351–373.

- Cabanes, Pierre. Les Illyriens de Bardylis à Genthios: IVe au IIe siècle avant J.-C. Paris, 1988.

- Gjongecaj, Shpresa. Emisione të reja monetare nga qyteti antik i Shkodrës (Scodra) [New coin emissions from the ancient city of Shkodra (Scodra)], Iliria 40 (2016), 97–109. DOI: 10.3406/iliri.2016.2517 https://doi.org/10.3406/iliri.2016.2517

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford, 1992.

- Group of Authors. Ilirët dhe liria tek autorët antikë [The Illyrians and freedom among ancient authors]. Prishtina, 1979.